I first noticed the connection in the late afternoon around the Sultanate’s area in Zinder, the Republic. The call to prayer had just faded, leaving behind a soft echo that blended with the sound of sandals on sand. Men emerged from the mosque slowly, wrapped in long, pale garments that caught the wind the way desert birds catch air. The cloth moved before the body did. It was familiar. Almost unmistakable.

This silhouette is not new to me; years earlier, I visited the Arabian Peninsula, where the thobe is not a fashion statement but a daily uniform of dignity. Standing there in the Sahel, with dust in the air and the scent of leather and tea drifting from nearby stalls, I realised something important: this was not a coincidence.

As a fashion and lifestyle writer covering African and Arabian culture, I have spent years tracing how garments travel not through trend cycles, but through people.

In this essay, I traced how the Arabian thobe travelled from the Arabian Peninsula to African cities and how it influenced men’s appearances in Niger, Northern Nigeria, and Sudan. Let’s explore Threads of the Desert: How Arab Thobes Shaped Sahelian Men’s Outfits, and what that influence reveals about trade, faith, climate, and shared knowledge.

You will learn:

- How the thobe’s design logic fits Sahelian life

- Why men’s robes in West and Central Africa look the way they do today

- How local cultures adapted, not copied, Arabian dress

- Why do these garments remain powerful symbols of identity

This is not a story of imitation. It is a story of conversation across deserts.

From Arabian trade routes to Sahelian royal courts, this is the story of how the thobe, simple, flowing, and purposeful, reshaped men’s traditional dress across Niger, Chad, and Northern Nigeria through climate wisdom, faith, and cultural exchange.

The Thobe’s Original Logic: Desert Intelligence

The thobe was born in the heat. Long before borders, it was shaped by sun, sand, and survival. Its loose cut allows air to circulate; its length shields the skin; its simplicity resists excess.

In Arabia, elders often say clothing must cooperate with the land.

A retired tailor in Al-Ahsa once told me:

“If your clothes fight the heat, you will lose the day before noon.”

This logic resonated deeply in the Sahel, where Niger, Chad, and Northern Nigeria share similar environmental realities. When Arabian garments arrived through trade and pilgrimage, people recognised not their foreignness but their familiar wisdom.

The Thobe was not created for fashion; it was for a purpose.

Trade Routes That Carried More Than Goods

The thobe did not arrive by ship alone. It moved through trans-Saharan trade routes, carried by merchants dealing in salt, leather, textiles, and books. Alongside commerce came habits, how to dress, how to host, how to pray.

In Kano, an old dye trader explained:

“Traders didn’t just sell cloth. They showed how to wear it.”

These routes are linked:

- Arabian ports

- North African cities

- Sahelian kingdoms

Over time, the thobe’s silhouette blended with local robes, giving rise to garments that felt both Islamic and indigenous.

Niger and Chad where the Thobe Meets the Sahel

In Niger and Chad, men’s traditional dress often features long, flowing robes with minimal tailoring, garments designed for heat, prayer, and movement. While names and decorations vary, the thobe’s structural influence is apparent.

Local adaptations included:

- Wider sleeves for airflow

- Thicker cotton for dust protection

- Earth-toned colours suited to the landscape

I met an elder in Nyame N’Djamena who reflected and said:

“Our clothes learned from the desert, just like we did.”

In the Sahel, every cloth, every piece of attire was designed for a purpose, not just for fashion: from protection to cultural identity.

Therefore, here, the thobe was not replicated stitch for stitch. It was translated into the Sahelian language.

Northern Nigeria: Authority, Embroidery, and the Babban Riga

In Northern Nigeria, the thobe’s influence becomes most dramatic. Over centuries, it contributed to the evolution of the Babban Riga, a wide-sleeved outer robe worn by emirs, scholars, and elders.

While structurally related to the thobe, the Babban Riga reflects:

- Hausa court culture

- Bold embroidery as social language

- Layered dressing for a ceremony

In my discussion with an elder in Zaria Palace, he said:

“When an emir enters, his robe speaks before he does.”

The thobe provided the foundation. Northern Nigeria added authority, clarity, and artistry.

Also Explore:

- Dressing for Heat: How Arab Design Principles Shaped Climate-Smart African Fashion

- Majlis Culture and African Courtyards: Shared Lifestyle Traditions Between Arabs and Africans

- Why Modesty Became Power: The Cultural Significance of Loose Clothing for Afro-Arab Women

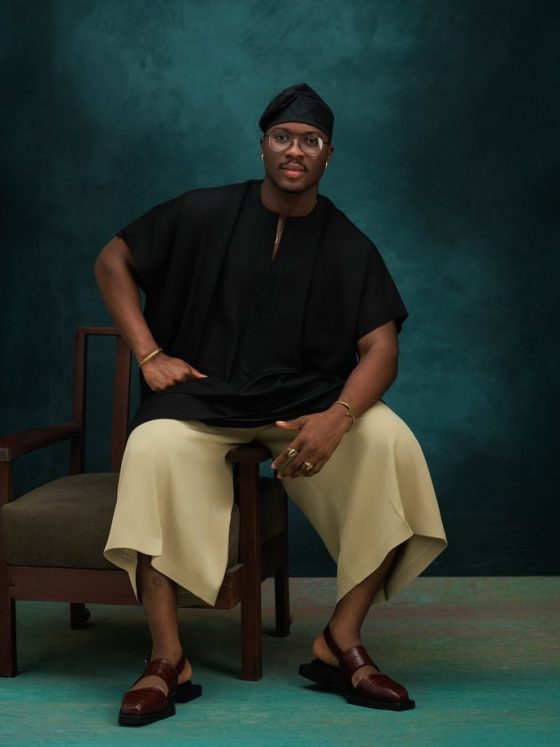

What the Thobe Looks Like

Most thobes feature long sleeves and a narrow collar, which may be round, standing, or slightly pointed depending on regional style. A short buttoned placket often runs from the neckline to the chest, adding both function and subtle decoration. In some traditions, a thin tassel (tarboosh) hangs from the neckline, a small but symbolic detail associated with refinement and heritage.

In colour, the thobe is most commonly seen in white, especially in Gulf regions, where lighter shades reflect sunlight and reduce heat absorption. However, in other contexts, particularly outside Arabia, thobes may appear in cream, beige, grey, indigo, or earth tones, aligning with local aesthetics and dye traditions.

The fabric is typically lightweight cotton, linen, or wool blends, chosen for breathability and durability. While everyday thobes are often plain, ceremonial or high-status versions may include delicate embroidery around the collar, cuffs, or chest, signalling social standing, scholarship, or religious authority.

Overall, the thobe’s appearance balances modesty, practicality, and quiet elegance—qualities that made it easily adaptable beyond Arabia and influential in shaping men’s traditional dress across the Sahel.

As evening fell in Zinder, the same men I had seen earlier returned home. Their robes carried dust, prayer, and the memory of the day. Watching them, I thought again of Arabia, of courtyards, quiet greetings, and cloth moving with the wind.

The thobe’s influence in Niger, Chad, and Northern Nigeria is not about imitation. It is about recognition, a shared understanding that good clothing listens to land, faith, and community.

If you’re curious about Afro-Arab fashion, visit Omiren Styles. We document these stories because we believe fashion is not a trend; it is knowledge passed hand to hand.

Explore more deeply reported stories on Arabian and African fashion, lifestyle, and history at omirenstyles, where clothing is culture and culture is never silent.

FAQs

1. Is the thobe originally African or Arabian?

The thobe originated in the Arabian region but influenced African dress through trade and cultural exchange.

2. Why do men’s robes in Niger and Chad resemble the thobe?

Both regions have desert climates and Islamic traditions that favour loose, modest clothing.

3. Is the Babban Riga the same as a thobe?

No. It evolved locally but was inspired by similar principles of structure and modesty.

4. Are these garments religious clothing?

They are cultural garments aligned with religious values, not religious uniforms.

5. Why have these styles survived modern fashion trends?

Because they solve practical problems, heat, dignity, and identity better than most modern designs.