I first understood the quiet authority of a Fulani turban on a dusty afternoon somewhere between Gashua and Geidam. The dry harmattan wind rolled across the savannah like an invisible tide, lifting grains of sand that shimmered briefly before settling on the road. I had stopped near a settlement where cattle bells rang with their soft, familiar clinks, metallic notes hanging in the still air like punctuation marks in a long, ancient sentence.

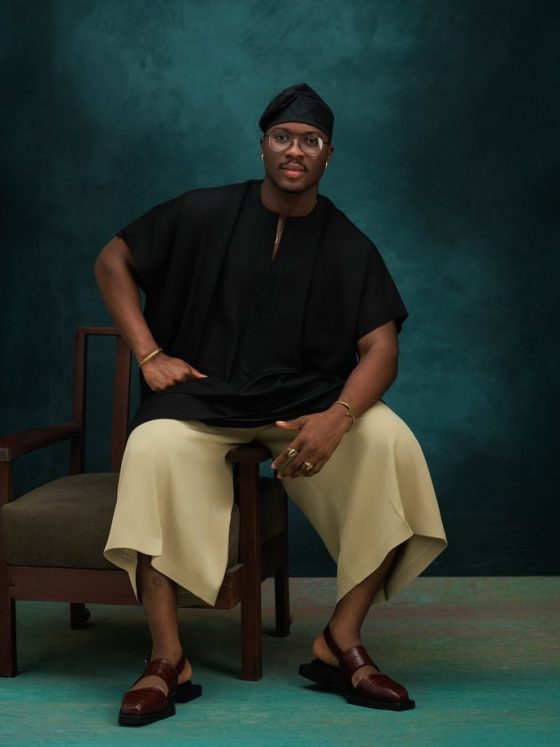

A group of Fulani men approached the watering point, their steps light and measured. What drew my eyes wasn’t the cattle, nor the rhythmic whistles the herders used to guide them, but the men themselves: tall, dignified, wrapped in layers of fabric that seemed to both defy and embrace the sun.

Their robes, flowing, embroidered, and almost weightless, danced with every stride. Their turbans sat like crowns: carefully wound, structured, and exact. Up close, I could see the fine dust caught in the folds, the faint scent of leather from the straps of their saddlebags, and the coolness of indigo dye that seemed to hold its own shade of evening.

In that moment, I understood why Fulani clothing is never just clothing.

It is a presentation. Preservation. Pronouncement.

This essay is my attempt to unravel that layered identity, stitched through centuries of movement, resilience, and elegance.

Discover how Fulani men’s turbans and robes reflect their dignity, identity, and cultural heritage across West Africa. Explore their history, symbolism, and timeless style.

Origin of the Turban: The Cloth That Journeys

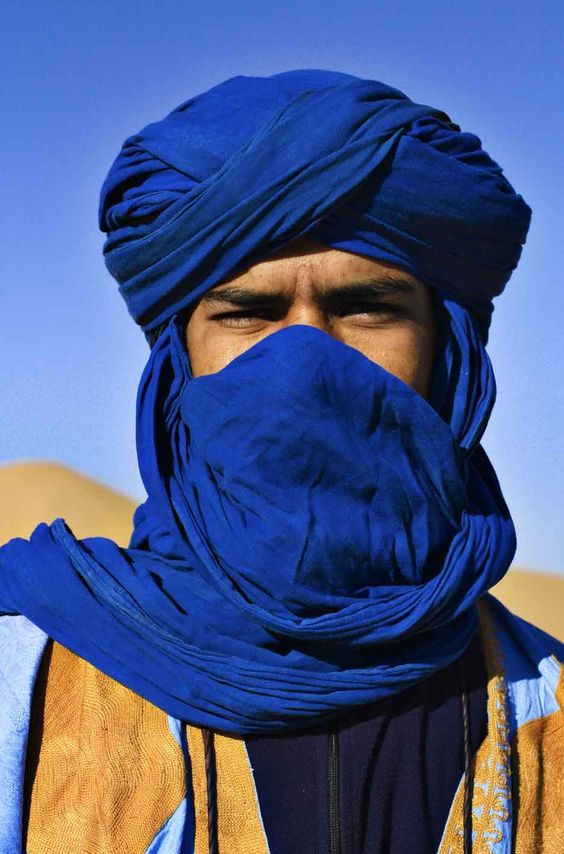

The Fulani turban, known in some communities as tagelmust , did not emerge from vanity. Its origin is rooted in necessity: the desert sun, the biting harmattan, and the need for protection during long migrations.

In a Fulani encampment near Gombe, an elder named Mallam Gidado told me,

“Our turban is our first shield. Before the spear, before the stick, this cloth guards a man.”

Wrapped around the head, nose, and neck, the turban protects against dust storms and insects. But its deeper value lies in what it symbolises: maturity, responsibility, and calm authority.

Travelling with nomadic groups, I noticed how each young man learns to tie his turban not from a manual but from watching fathers, uncles, and elders. Each winding carries memory; some knots are used during travel, others during ceremonies, and some only for courtship or funerals.

It is a moving archive, worn daily yet never ordinary.

Robes of Respect: The Elegant Economy of Motion

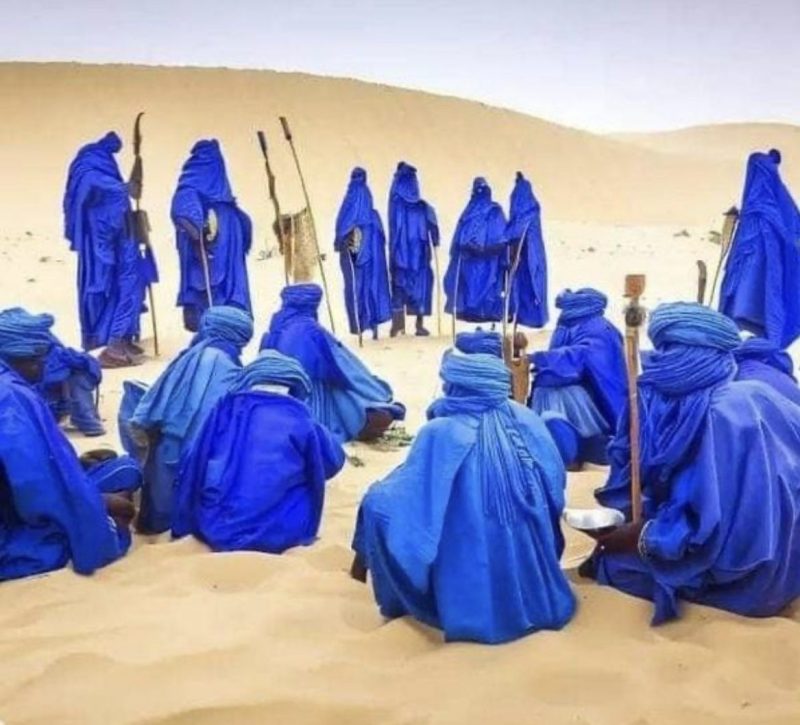

Fulani robes, whether the richly dyed babanriga, the lightweight zani, or the nomadic riga, are crafted for movement. Their silhouettes expand in the wind, almost echoing the wide landscapes the Fulani traverse.

At a cloth-dyeing pit in Yola, a young artisan named Hauwa described their secret:

“A Fulani man must walk as if the sky is watching. His robe helps him remember that.”

The robes use flexible cotton, designed to keep the body cool despite the heat. Indigo, the preferred dye, was historically a sign of prestige across Sahelian empires. The deeper the blue, the more esteemed the wearer.

I watched as a Fulani herder adjusted his robe before mounting his horse, the cloth rippling in the light breeze. It looked almost ceremonial, yet entirely practical. The robe’s length shields the skin; its width maintains airflow; its folds hold small items like prayer beads or herbs.

Turban Etiquette: When Cloth Becomes Identity

In many Fulani communities, how a turban is tied communicates everything: age, status, temperament, and even emotional state. The front fold can signify readiness for travel; a fully wrapped mouth may signal a solemn mood; a loosely arranged top might hint at a casual gathering.

A trader in Nguru, Jamilu, laughed as he showed me the styles:

“If a man ties it too tightly, he is inexperienced. If he ties it too loosely, he is careless. A man must balance his clothes the way he balances his life.”

This understated philosophy reveals the true depth of Fulani attire; it is a living code of self-regulation.

Even during disputes, a man’s turban remains composed. As one elder put it,

“You cannot raise your voice if your turban is calm.”

ALSO READ:

- Beads, Bangles, and Braids: The Signature Beauty of Fulani Women

- Kanuri Royalty: The Traditional Fashion of Borno’s Ancient Nobility

- 5 Best Traditional Caps for Northern Nigerian Men in 2025.

Ceremony, Power, and Public Image

In weddings, naming ceremonies, and cattle festivals like the Gerewol, turbans and robes transform into statements of lineage and influence.

Patterns grow bolder. Embroidery becomes more ornate. Turbans are layered into elegant peaks.

At a wedding in Hadejia, I observed the groom’s procession, a slow, rhythmic parade of pride. His robe billowed like a sail of ancestry, embroidered with motifs representing cattle horns, stars, and symbols of blessing. His turban glowed white against the reddish evening sky.

A middle-aged woman whispered to me,

“We see a man’s discipline in his dressing. A robe can tell you if he respects his father.”

In Fulani culture, beauty and discipline intertwine. Clothing becomes testimony.

As I left the settlement near Gashua, the sun dipped behind the acacia trees, casting long shadows on the road. A young herder waved, his turban glowing softly in the last light of day, his robe fluttering like a quiet flag of identity.

I realised then that Fulani clothing is not merely woven thread; it is presence.

It is the unspoken poetry of men who walk with the confidence of their ancestors and the calm of those who know exactly who they are.

And perhaps, in a world where identities often shift like sand, the Fulani turban stands as a reminder: dignity is not declared. It is worn, layer by layer, knot by knot, step by step.

FAQs

1. Why do Fulani men tie turbans even in hot weather?

Because the turban is designed for protection, not warmth. It shields them from heat, dust, insects, and glare. The cotton allows air to flow, making it surprisingly cool.

2. Do all Fulani men tie the turban the same way?

Not at all. Variations span families, regions, and even personal mood. The way a turban sits can signal age, experience, or social standing.

3. Are Fulani robes only worn during ceremonies?

No. Everyday robes exist, usually plain and lightweight. Ceremonial robes are more ornate and reserved for weddings, festivals, and important gatherings.

4. What colours are most respected?

Indigo holds the highest prestige historically, but white is associated with purity and dignity, especially in formal events. Earth tones appear in nomadic settings due to practicality.

5. Can non-Fulani people wear Fulani turbans?

Yes, if done respectfully. Many travellers, researchers, and friends of Fulani communities are gifted turbans. But always wear them with cultural appreciation, not costume-like intent.