I still remember the first morning I spent in a Fulani settlement outside Toro, Bauchi State. The air smelled of woodsmoke and fresh cow milk, the kind that carries a soft sweetness only nomadic life can produce. Children chased each other around clay huts, their giggles rising like birdsong. But what held me still was the slow, deliberate ritual of adornment unfolding in front of me.

A young woman named Fatima sat on a low stool as her aunt separated sections of her hair. The sound of the comb sliding through her thick, dark strands was rhythmic, almost ceremonial. Coloured beads lay in a calabash bowl, glowing in the morning sun, red like desert berries, gold like dry season grass, and turquoise like faraway rivers. Every bead felt like a memory shaped into a colour.

Her bangles clinked softly as she lifted her arm, thin brass ones worn high on the forearm, heavier coiled ones closer to the wrist. “These are not just to look pretty,” her aunt told me in Hausa. “They are our map. They show where we come from. Who raised us? The path our grandmothers walked.”

As the braids grew, her aunt tightened each one with the practised pull of someone who had repeated this motion for decades. The textures, the sounds, the gentle smell of shea butter warming under the sun, it all made me understand something instantly: Fulani beauty is not cosmetic. It is cultural, communal, and deeply historical.

That morning became my entry point into a world where adornment is storytelling, and Fulani women are its most powerful authors.

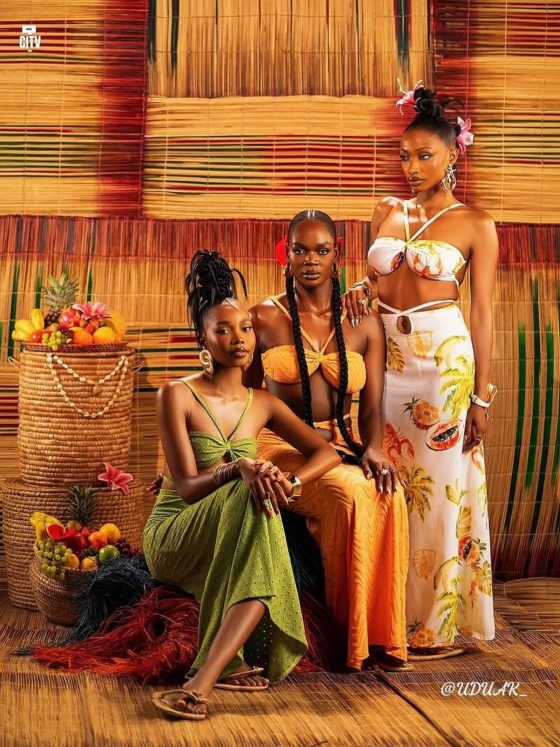

A journey into the sunlit world of Fulani femininity, where beads whisper ancestry, bangles echo migration routes, and braids tell stories older than borders. This is the living artistry of Fulani women, a beauty shaped by movement, memory, and meaning.

The History in Their Hair: Origins of Fulani Braiding

Fulani braids trace back centuries, carrying far more than beauty. In ancient Fulani communities, every pattern served a purpose, signalling clan identity, marital status, migration paths, and even the turning of the seasons. Each braid was a story, woven with intention.

Elder Ya Husseina in Yola told me,

“Fulani braids are like our signatures. Every pattern has a meaning, and every meaning has a story behind it.”

Some braids mimic the curve of cattle horns; others reflect ripples of dried riverbeds crossed during migration from Senegal through Niger, Cameroon, Guinea, and beyond. This is why no two Fulani groups braid the same.

I watched a group of teenagers practice braiding during Harmattan. Their fingers moved so quickly that the air whistled as they pulled and looped each strand. One girl told me a secret:

“We learn by touching hair, not by watching. It is the hand that remembers.”

From my research, I observed that the Majority of Fulani women know how to create beautiful braided styles.

Beads That Speak in Colour

Fulani beads are never chosen at random. Every colour, every material carries meaning. Amber symbolises protection on long voyages. Coral celebrates womanhood and fertility. Blue glass beads honour ancestry and spiritual guidance. Even the way they’re arranged can signal joy, mourning, or rites of passage. In Fulani culture, beads are more than adornment; they are a living archive of memory, status, and identity.

- Amber beads: believed to bring luck and protection.

- Coral beads: symbols of fertility and womanhood.

- Cowrie shells: ancient symbols of wealth and blessing.

- Blue glass beads: linked to water spirits and memories of migration.

In Kano’s centuries-old Kurmi Market, I met Baba Joda, a bead seller whose father and grandfather traded beads with Tuareg caravans.

He lifted a string of amber beads and said,

“These travelled farther than most people in this market. Some came from Morocco. Others came from Mali. Fulani women wear journeys around their necks.”

Bangles as Identity, Status, and Sound

Fulani bangles are among the most recognisable elements of their adornment. They often wear multiple metal bangles at once, brass, silver, and sometimes leather-wrapped ones for young girls.

In Gombe, a woman showed me bangles passed down from her grandmother.

“She wore these when she married my grandfather. He was a cattle merchant. She said the sound of her bangles was the sound of her new home.”

To this girl, the bangles are not just meant for fashion; they are the identity of her historical ancestors.

What struck me most was the music of Fulani jewellery. When women walk, their bangles create a soft, ringing melody (Cral! Cral!!), a sound that travels ahead of them, announcing their presence.

ALSO READ:

- 5 Best Traditional Caps for Northern Nigerian Men in 2025.

- Latest 5 Ankara Outfits for Hausa Women in 2025

- The New Face of Modesty: Modern Abaya and Hijab Trends in Northern Nigeria

Beauty as Mobility: Why Fulani Aesthetics Are Designed for Movement

The Fulani are a people shaped by movement, seasonal migration, cattle routes, and shifting landscapes.

- Lightweight beads that won’t hinder travel

- Braids that stay neat for weeks

- Bangles that double as identity markers during nomadic gatherings

A young mother in Jibia, Katsina, told me:

“Even when we move, beauty moves with us. We don’t stop being ourselves.”

Embedded in this quote is a cultural principle: among the Fulani, beauty is never just decoration. It must be functional, durable, and expressive, a practical art form shaped by geography, tradition, and the demands of travelling.

As the sun dipped over the settlement that day in Toro, the final bead clicked into place on Fatima’s braid. Her aunt stepped back, admiring her handiwork as an artist might a finished sculpture. The air smelt of dusk and cowhide, and the soft clinking of bangles drifted through the compound like a fading lullaby.

Watching her stand tall, confident, and luminous, I realised that Fulani beauty is not just visible. It is felt. It is heard. It is carried.

And like those beads strung together across centuries, the story of Fulani women continues to glow, one braid, one bangle, one journey at a time.

FAQs

1. Why do Fulani women wear so many beads?

The reason is that beads symbolise memory, migration stories, blessings, and lineage. Many are heirlooms passed down through generations.

2. Are Fulani braids complex to create?

Yes and no. The technique is precise and requires training, but skilled hands can braid a complex Fulani pattern in under an hour. It’s a craft of muscle memory.

3. Is it appropriate for non-Fulani women to wear Fulani-inspired hairstyles?

Yes, as long as it’s done respectfully, with credit given to the culture, and without commercial exploitation.

4. What materials are Fulani bangles made from?

Traditionally, brass and silver are used, but in some regions, leather, copper, and coiled metal are also used.

5. Why is adornment so important in Fulani culture?

This is because the Fulani people express their identity through their beauty. Their aesthetics reflect mobility, spirituality, lineage, and womanhood.