The first time I noticed it, it was the smell before the sight.

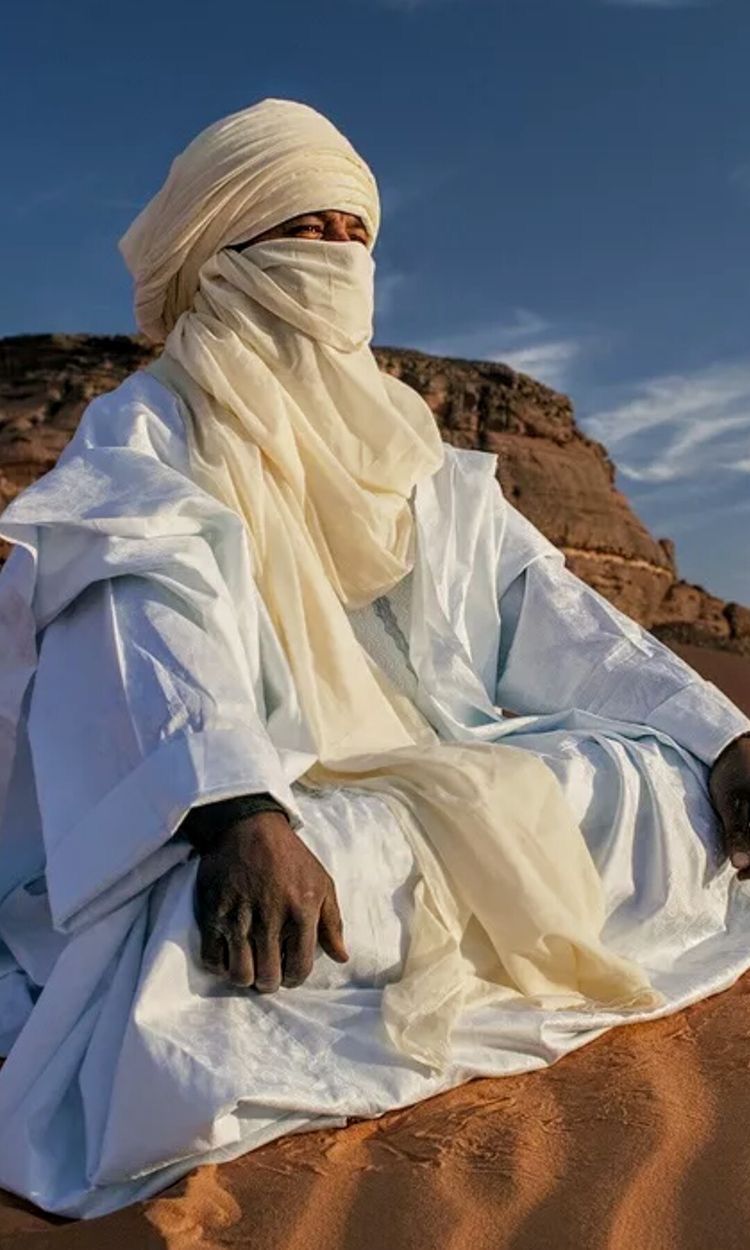

It was a Wednesday afternoon at Kantin Kwari Market in Kano State, and the sharp, earthy scent of indigo dye hung thick in the air. That familiar aroma was more than just a smell; it was a quiet reminder of a craft that has shaped West African identity for centuries, binding generations of artisans, traders, and cultures through cloth, colour, and tradition. Traders unrolled thick, hand-dyed fabrics onto worn wooden tables, their palms permanently stained blue from years of working with indigo leaves fermented in clay vats. The transaction was not merely commerce; it was continuity. In the market, a man’s carefully folded turban, both functional and architectural, and his robe, familiar yet subtly foreign, reflected centuries of desert wisdom and cultural exchange between Northern Nigeria and the Arabian Peninsula.

This resemblance was no coincidence. For centuries, Kano sat along vital caravan routes linking West Africa to North Africa and the Middle East. Through trade, pilgrimage, and scholarship, especially along the Hajj routes to Mecca, ideas travelled alongside gold, leather, salt, and cloth. Arabian dress sensibilities blended with Hausa tailoring, producing styles that felt local yet cosmopolitan. The turban became both a spiritual symbol and a cultural bridge; the robe, a quiet archive of shared histories.

As someone who has grown up between Northern Nigeria and the wider Islamic world, I have seen this influence all my life, long before I had the language to name it. Arabian fashion did not arrive in Hausa and Sahelian societies as an imitation. It came through exchange, faith, trade, scholarship, and movement.

What we wear here is not borrowed. It is inherited, adapted, and deeply rooted.

A deep cultural exploration of how Arabian trade, faith, and migration shaped Hausa and Sahelian fashion through textiles, silhouettes, modesty, and shared desert identity.

The Story and Its Living Threads

Trade Routes That Intertwined Styles Across the Sahara

Fashion evolved in response to trade long before it began to follow trends.

For centuries, trans-Saharan trade routes connected the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, and the Sahel. Salt, gold, leather, books, and textiles were moved across deserts by camel caravans. With them came clothing ideas: flowing robes, turbans, and layered garments designed for heat, dust, and dignity.

An elderly trader in Zinder once told me, “Cloth travelled with belief. You could see where a man had been by how he dressed.” Arabian fabrics and silhouettes were not imposed; they were welcomed because they made sense in the Sahelian climate.

Loose garments protected the skin. Head coverings shielded from the sun and sand. Fashion followed function, and function followed geography.

Faith as a Fashion Bridge

Islam became one of the strongest connectors between Arabia and the Hausa-Sahelian world. With faith came shared ideas of modesty, cleanliness, and presentation.

The long robe, whether called a jalabiya, kaftan, thobe, or riga, became common across regions and was adapted to local tastes. In Hausa land, embroidery grew bolder. Necklines became wider, sleeves fuller. Yet the underlying form remained unmistakably Arabian in origin.

A Qur’anic teacher in Katsina once explained it simply: “We dressed like those we learnt from, but we made it our own.”

Faith did not erase culture. It was layered onto it.

The Turban: From Arabian Desert to Sahelian Identity

Perhaps no item shows this cross-cultural journey more clearly than the turban.

In Arabia, it was protection against the sun, sand, and wind. In the Sahel, it became symbolic. Among Hausa and Tuareg communities, the turban signified age, scholarship, authority, and masculinity.

I once witnessed the elders wrapping a young groom before a wedding ceremony. Each fold was intentional. Each turn carried meaning. “You are not just covering your head,” an elder murmured. “You are carrying history.”

The turban did not arrive unchanged. It evolved thicker fabrics, deeper indigo dyes, and regional wrapping styles, yet its Arabian roots remain visible.

Tailoring as Cultural Translation

Arabian garments met Sahelian tailoring, and something new emerged.

Local tailors expanded silhouettes, intensified embroidery, and adjusted cuts to suit ceremony and status. Where Arabian robes leaned toward minimalism, Hausa fashion leaned toward expression, bold patterns, geometric designs, and symbolic stitching.

In a small workshop in Sokoto, a tailor once showed me an old design book passed down through generations. “The idea came from Arabia,” he said, “but the voice is ours.”

Fashion became a language spoken fluently across borders.

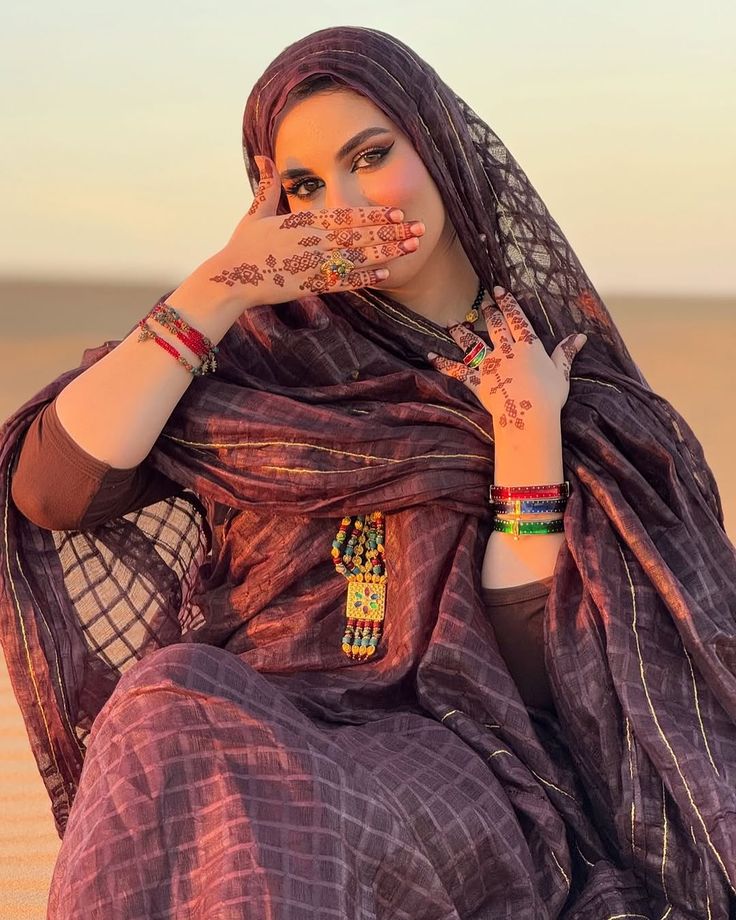

Women and Arabian fashion

In regions such as the Sahel, the Swahili Coast, and parts of North and West Africa, flowing silhouettes, modest layering, and structured head coverings became integrated into local styles. Garments like wrapped veils, loose-fitting gowns, and embroidered abayas were reinterpreted using indigenous fabrics, hand-dyed textiles, and regional motifs. This fusion allowed women to express faith, status, and cultural belonging while maintaining comfort in hot climates.

Beyond clothing, these influences shaped how African women used fashion to express identity and dignity. Dress communicated spirituality, marital status, age, and social responsibility. Over time, African women transformed external influences into distinctly local expressions, proving that cultural exchange in fashion is not passive imitation but an active process of creativity, resilience, and self-definition.

RECOMMENDED:

- The Jalabiya: How a Desert Robe Became a Global Summer Staple

- Turbans and Headwraps: How an Arabian Headpiece Found a Second Home in Africa

- Keffiyeh Scarf: A cultural identity that became streetwear fashion

Modern Identity and Global Recognition

Today, Arabian-influenced Hausa and Sahelian fashion is attracting growing global attention. International designers increasingly reference its silhouettes, textiles, and draping techniques on global runways, while social media platforms introduce these styles to audiences far removed from their geographic and cultural origins. This renewed visibility reflects a broader recognition of Africa’s historical role in shaping global fashion narratives.

At the local level, however, the meaning of these garments remains deeply rooted in everyday life and spiritual practice. They are worn for prayer, weddings, naming ceremonies, and daily activities, serving practical, cultural, and religious functions. Rather than existing solely as decorative or symbolic attire, they represent lived traditions passed down through generations.

As global fashion continues to search for authenticity and heritage-driven design, the Sahel offers an important lesson: cultural influence does not erode identity. Instead, when traditions are preserved and adapted on their terms, influence becomes a source of strength, continuity, and cultural resilience.

As the sun dipped low over Kano that morning, the market slowly quieted. The sharp scent of indigo softened in the cooling air, and traders began folding their fabrics with care and intention, handling cloth not merely as merchandise but as vessels of memory, skill, and heritage passed down over generations.

These exchanges shaped how people dressed, not to imitate, but to adapt, refine, and express identity within their own cultural frameworks.

Every fold of cloth, every stitch of embroidery, and every carefully wrapped turban carries a history older than modern borders. They speak of caravan routes, pilgrimage trips, and communities that learnt from one another while remaining firmly rooted in their own traditions.

To explore more stories where fashion, culture, and history intersect with depth, accuracy, and respect, visit Omiren Styles, where style is not only worn, but understood

FAQs

1. Is Hausa fashion copied from Arabian culture?

No. It is shaped by exchange, not imitation. Arabian influence blended with local aesthetics to form something distinct.

2. Why are robes so standard in both regions?

Climate, faith, and mobility made loose garments practical and meaningful across deserts and savannahs.

3. Are these styles still relevant for young people?

Yes. Many designers modernise traditional forms while maintaining cultural integrity.

4. What role did trade play in the fashion exchange?

Trade routes acted as cultural highways, moving textiles, ideas, and craftsmanship across regions.