After years of marginalisation, black fine art is finally receiving the attention and price tags it deserves. Take Swann Galleries, for example. Back in 2006, Nigel Freeman launched the African American Art department. It’s still the only big auction house with a whole team devoted to African American art, and their sales keep smashing records. Just look at the numbers: Richmond Barthé’s Feral Benga sold for $629,000, Elizabeth Catlett’s Head pulled in $485,000, and Hughie Lee-Smith’s Aftermath hit $365,000. These aren’t just impressive figures; they’re proof that the art world is waking up. People are finally acknowledging that Black artists are on par with the industry’s most valuable names. This isn’t some passing craze. It’s a fundamental shift, correcting prices that racism kept artificially low for generations.

Explore how Black fine art auctions are transforming the art market through record-breaking sales, institutional recognition, and cultural reclamation.

What’s Driving the Record-Breaking Sales?

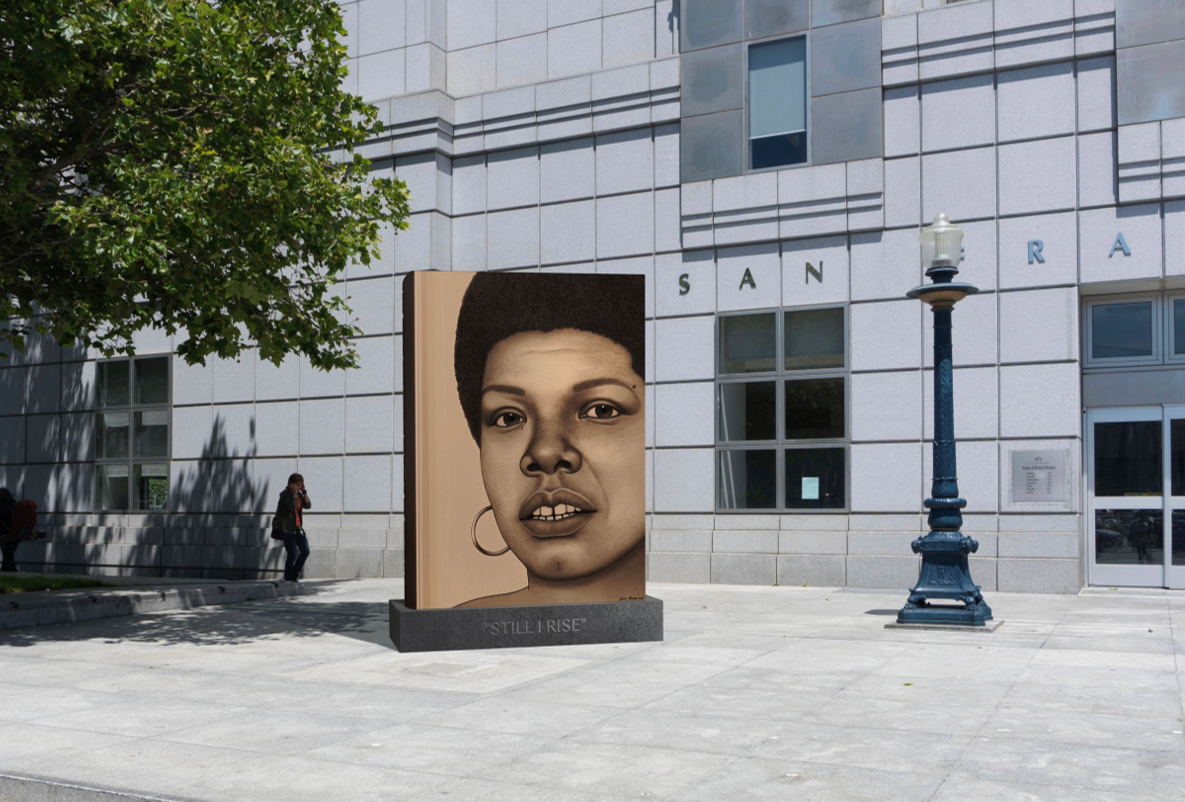

If you watched Phillips’ contemporary art sale, you saw it in action. They brought in $134.6 million from just 31 lots, and five new auction records were set for African American artists like Amy. The artists involved are Sherald, Kehinde Wiley, Mickalene Thomas, and Vaughn Spann. Sherald’s The Bathers sparked a 15-minute bidding war and landed at $4.4 million, while Wiley’s Portrait of Mickalene Thomas, the Coyote, sold for $378,000.

So, what’s behind this surge? It’s not just one thing. The Black Lives Matter movement made museums and collectors look hard at who’s really represented in their collections. Suddenly, museums scrambled to buy Black fine art, which drove up prices. Plus, you’ve got a new generation of collectors, more diverse and more intentional, who are determined to support Black artists and undo some of that old exclusion. Online auction platforms helped, too, opening the doors for people all over the world to get in on sales that had been closed off to tight-knit, mostly white circles.

Sherald and Wiley entered the mainstream and revolutionised it. The world took notice when the National Portrait Gallery selected them to paint official portraits of Michelle and Barack Obama. That kind of recognition changed their careers overnight and showed just how much institutional support can boost Black fine art at auction.

The Infrastructure Behind the Market

Look at some of the collections Swann has brought to auction: Dr. Maya Angelou’s art, the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company collection, and the Johnson Publishing Company’s trove (their first white-glove sale). These weren’t random finds. They were built by institutions that believed in Black art long before the mainstream caught on. Now, as those collections hit the auction block, they’re setting the pace for today’s prices.

And here’s the thing: building real infrastructure matters. Establishing departments dedicated to Black fine art sends a clear message: this work merits the same expertise, attention, and investment as Impressionist or Contemporary art. That shift in attitude and resources is what finally moves Black fine art out of the “outsider” label and gives it the respect it’s consistently earned.

READ ALSO

- 10 Environmental Activists Changing Our Planet’s Future

- African Royals as Cultural Ambassadors: Guardians of Heritage in a Modern World

- The Future of Luxury Modesty Fashion Trends in Africa for 2026

Why Are Museums Competing at Auction?

Museums are snapping up Black fine art at auction these days, and it’s about time. For years, most big museums basically ignored Black artists. They’d donate now and then but wouldn’t put real money behind building those collections. Now they’re stuck with galleries that don’t reflect art history as it really happened. So what’s the fix? Buy, and buy fast, but that means going head-to-head with private collectors, which drives prices through the roof.

This new surge of museum interest creates its own cycle. When museums buy a piece, it tells the world the work matters. That draws in private collectors who want something with museum-level credibility. The demand keeps climbing, prices follow, and so it goes. Look at the recent Sotheby’s auctions; every single piece donated to benefit the Studio Museum in Harlem sold, and many soared way past their top estimates. Collectors clearly see the artistic and cultural value, and they’re willing to pay for it.

Contemporary vs. Historical Black Fine Art

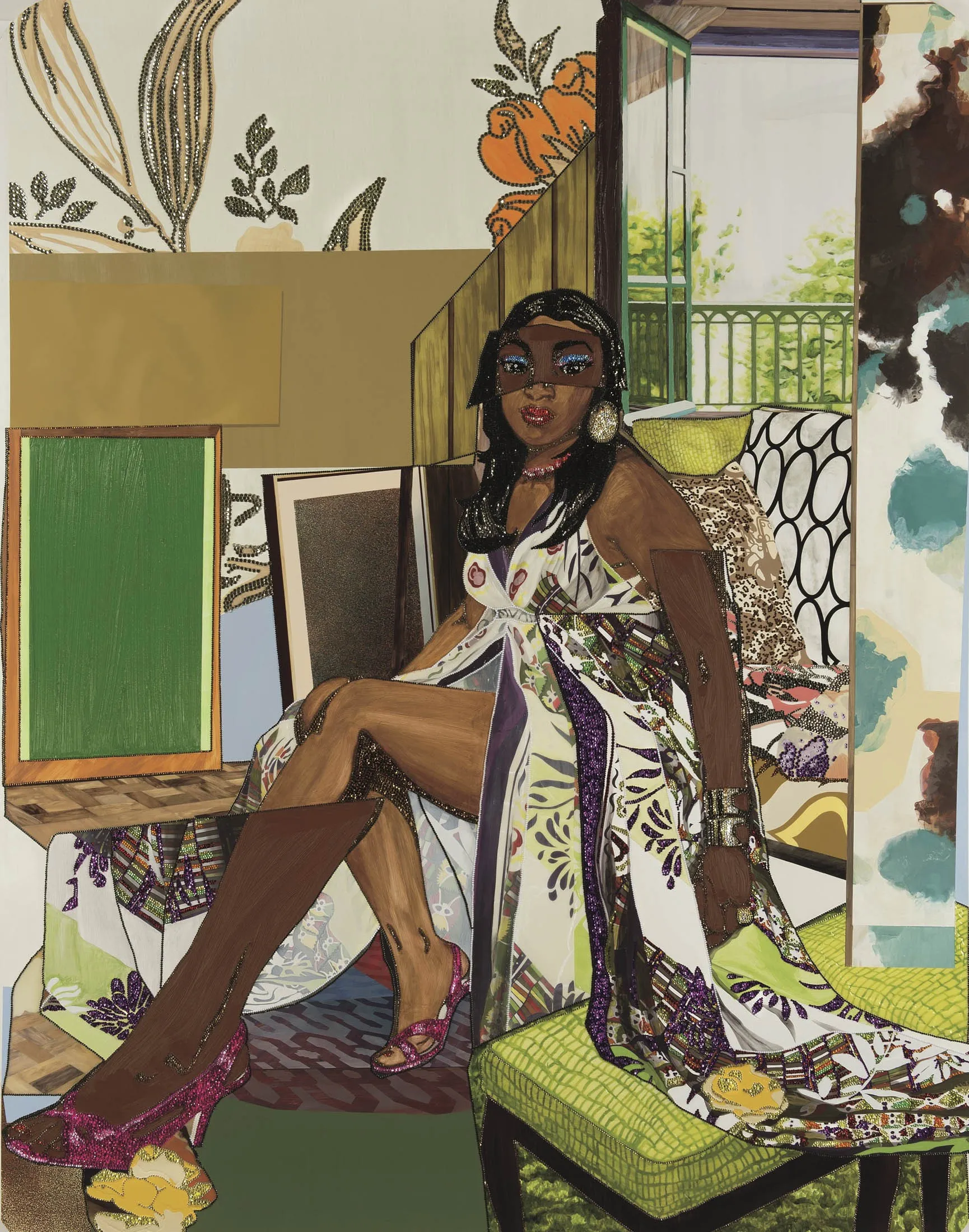

Take Mickalene Thomas’ “I’ve Been Good To Me.” It didn’t just beat expectations; it crushed them, selling for $901,200, almost double her previous record. Vaughn Spann’s “Big Black Rainbow (Deep Dive)” brought in $239,400. Contemporary Black artists are achieving the highest prices at auction right now, and it’s not hard to see why. Collectors like living artists they can meet, art that speaks to what’s going on today, and the fact that newer work often comes in bigger editions, making it easier to buy and sell.

But that doesn’t mean older work is getting left behind. Pieces from the Harlem Renaissance and mid-century modernists continue to climb steadily as more collectors recognise their rightful place in art history. Swann Galleries’ African American Art department covers everything from the late nineteenth century to contemporary artists, ensuring no era is overlooked.

How Does Institutional Recognition Affect Prices?

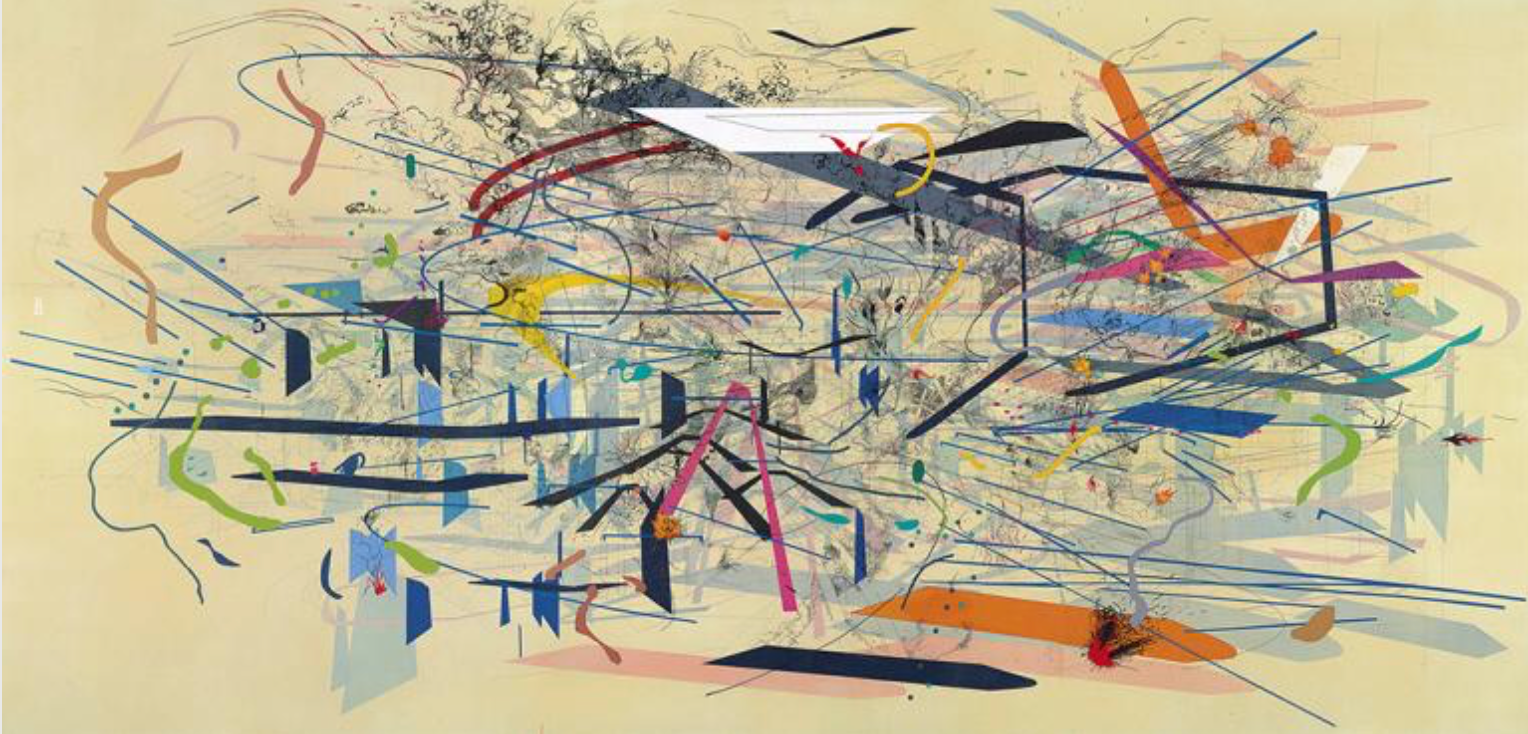

Look at Julie Mehretu. Her painting sold for $9.3 million, a record for an African-born artist, and for Black female artists in general. Why did it hit so high? This was mainly because museums had already established her as a prominent figure through significant retrospectives and positive reviews. When museums give an artist the spotlight, collectors take notice. It’s a signal: this work is here to stay, and its value will likely climb.

Barbara Chase-Riboud is another story. She’s been working for decades, making these beautiful, fluid sculptures with metal, silk, and wool, and honouring people like Malcolm X and Josephine Baker. Museums have celebrated her for years, but only recently has the auction market truly caught up. Occasionally, it takes a long stretch of museum support before prices really jump.

The Role of Dedicated Auction Platforms

It’s not just about the big auction houses anymore. New platforms have popped up that focus entirely on Black fine arts. These spaces give artists and collectors an alternative to the old-school auction world, which hasn’t always been welcoming. Lower fees, more inclusive curating, and a focus on Black aesthetics, not just as an add-on to Western art, but as the centre, make a big difference.

These specialised platforms have forced major houses to step up, too. Now there’s more competition, better representation, and real resources dedicated to Black fine art. Everyone wins, collectors get choices, artists get more ways to sell, and the whole market gets stronger.

What Challenges Remain?

Even with higher prices and more attention, there are still hurdles. Many historical Black artists continue to be underappreciated when compared to their white counterparts in similar professions. Black artists struggle to secure auction guarantees, which ensure art sells for a minimum price. Descriptions in auction catalogues sometimes rely on coded language or don’t explain why the work matters in the broader context.

Plus, the market can be pretty fickle. Black fine art may suffer more than established blue-chip items if museums lose interest or slash their budgets. Building a lasting market needs more than just a trend or a wave of enthusiasm; it takes steady support, even when the spotlight moves on.

Frequently Asked Questions

What’s pushing Black fine art to new price heights at auction?

A lot’s going on here. Museums are racing to fill gaps in their collections, especially where Black artists were previously excluded. There’s a fresh wave of collectors, young, more diverse, and definitely more visible. Big moments like the Obama portraits got everyone talking. The Black Lives Matter movement forced many people to pay attention. Additionally, digital platforms expanded their reach to include everyone, not just insiders. And let’s not forget that the auction houses themselves noticed the demand; now, many have teams that know this field inside out.

Which Black artists are setting records at auction?

There’s a real mix. Amy Sherald’s “The Bathers” sold for $4.4 million. Julie Mehretu hit $9.3 million; she now holds the record for the most expensive work by an African-born artist. Mickalene Thomas reached $901,200. Kehinde Wiley, $378,000. Richmond Barthé, $629,000. Elizabeth Catlett, $485,000. Hughie Lee-Smith, $365,000. So you’ve got both living artists and critical historical names making waves.

How are Black fine art auctions different from regular art auctions?

These auctions really need people who get the cultural background and the history behind the work. Understanding African American and African diaspora art isn’t just a bonus; it’s essential. There are connections between artists, collectors, and museums that general auctions just don’t have. Swann Galleries, for example, is still the only major auction house with a department focused just on African American art. That focus makes a difference. Their results prove it.

What is driving the recent enthusiasm among museums to acquire Black fine art at auction?

Museums are catching up. For years, they left out Black artists. Now, with more people demanding accountability, museums are rushing to fix their collections. They’re setting aside real money to buy Black fine art, going up against private collectors, and those bidding wars push prices up. When a museum buys a piece, it’s not just about money; it’s about saying, “This matters. This piece belongs in the story of art.”

What should new collectors know about Black fine art auctions?

Do your homework. See where an artist has exhibited, which museums have collected their work, what critics say, and how their prices compare. It helps to talk to advisors who actually know Black fine art. Because these artists were overlooked for so long, their work can still be relatively affordable compared to that of white artists with similar careers. While this presents an opportunity, it also underscores the significant task the market still faces in achieving fairness.