Hollywood’s cinematography world remained closed for nearly a century, excluding Black artists whose work, skill, and vision did not align with the industry’s narrow definition of “good.” People refer to their images as “underexposed” or “technically insufficient”, thereby overlooking their true significance and missing much of their beauty. Bradford Young, who’s made a name for himself recently, looks back at trailblazers like Ernest Dickerson (Malcolm X), Arthur Jafa (Daughters of the Dust), and Malik Sayeed (Clockers). These guys didn’t just turn on a camera. They built the groundwork for everyone who came after.

But here’s the thing: Black cinematographers in Hollywood aren’t just shooting films. They are retaliating against decades of neglect. They’re saying, Look, the way Black people are seen on screen – it matters. It shapes how we see ourselves and each other. These artists create new visual languages, drawing on their own lives rather than copying what film schools say is “right”. Their work is a kind of cultural activism, hidden in the details of light and shadow. Cinematography isn’t some neutral craft; it’s loaded with politics, with culture, with the question of who gets to decide what’s beautiful when it’s blown up on a cinema screen.

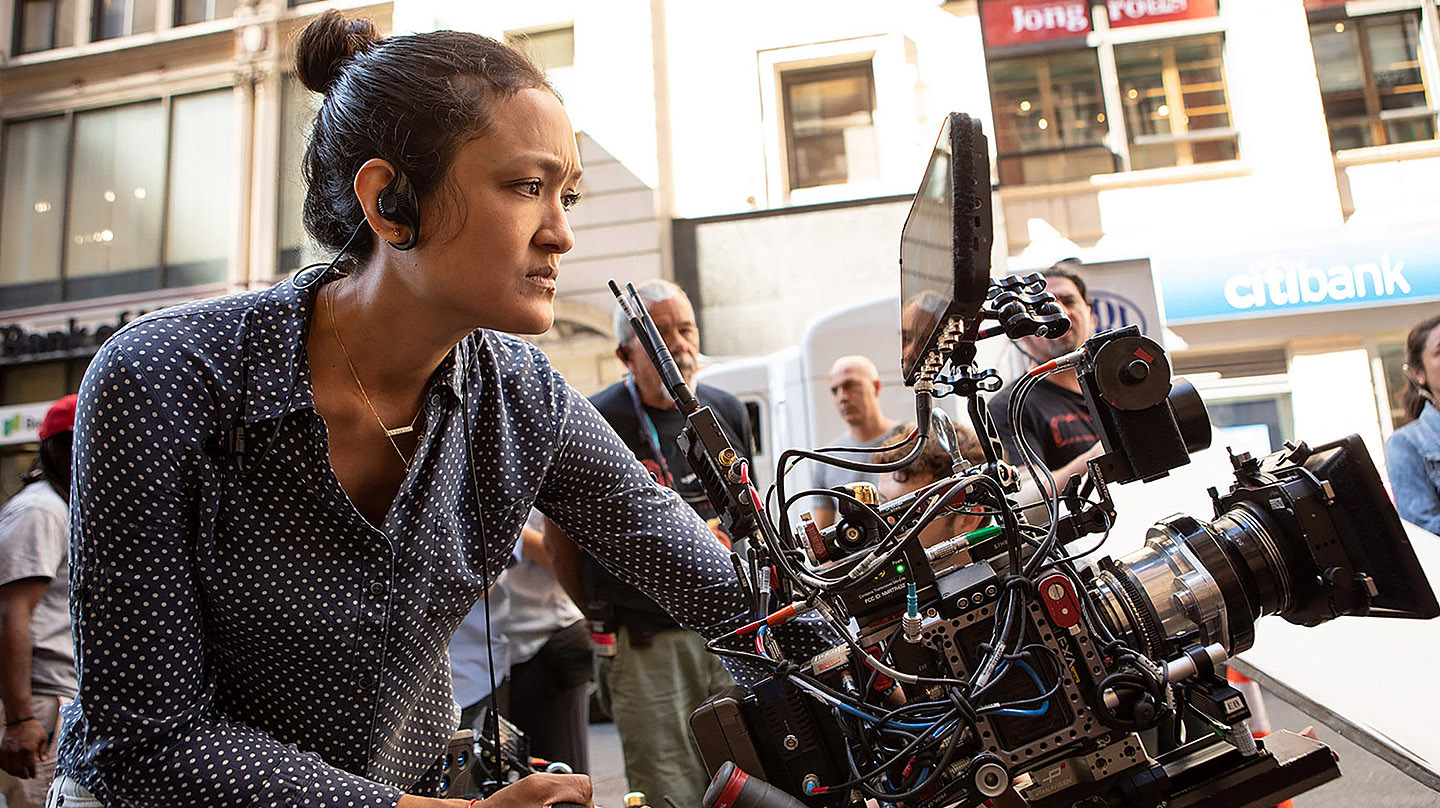

These 10 black cinematographers are revolutionising Hollywood through heritage-driven visual storytelling that challenges conventional techniques and redefines cinema.

Why Visual Representation Needs Cultural Awareness

Bradford Young once put it bluntly: “I’m never satisfied with the way I see my people photographed in films.” He said, “If you grew up somewhere you never really knew Black people, I wouldn’t expect you to photograph them with any real care.” That’s the heart of it. Black cinematographers matter for more than just numbers or diversity checkboxes. For Young, it’s personal. “Something like Selma, or Mother of George, or Pariah – I know those people. They’re my grandparents, my aunts and uncles, my cousins. When I see Alike or Martin Luther King, I see my family. I love my family, so I wouldn’t photograph them any differently.”

For these filmmakers, lighting Black skin isn’t just a technical issue – it’s a commitment. The tools of the trade, from film stock to exposure meters, were built for white skin. So Black cinematographers have to push back. They bring their memories and community wisdom into every shot they set up. Their expertise comes out of their lived experience, not in spite of it.

1. Ernest Dickerson, ASC – The Pioneer Who Defined a Generation

Ernest Dickerson collaborated with Spike Lee, transforming the film industry. Their films – Do the Right Thing, Malcolm X, and Jungle Fever – brought a whole new look to Black cinema. Bold colours. They employed unconventional angles. Lighting is about making you feel something, not just making things look “real.” Dickerson demonstrated his deep understanding of filmmaking by transitioning from behind the camera to directing. He showed that Black visual storytelling could draw on jazz, hip-hop, and the richness of the African diaspora, not just what Western critics called beautiful.

2. Bradford Young, ASC – Breaking the Academy’s 87-Year Drought

In 2017, Bradford Young became the first African American ever nominated for the Oscar for cinematography – almost hard to believe it took that long. He told Variety, “I still have many questions about why I am the ‘first’ African-American to be nominated for a cinematography award. In some ways, it’s deeply troubling to me.”

Young has a way with colour and light that’s all about closeness. He wants you right there, feeling what the characters feel. “You can’t create an emotional wavelength if you’re outside looking in,” he says. His work – Selma, Arrival, A Most Violent Year, When They See Us – shows how personal memory shapes every technical choice. When he gets stuck, he goes back to the feelings and images from his childhood. That’s where he finds the right answer. That’s how he knows he’s doing it right.

3. Arthur Jafa – The Artistic Visionary

Arthur Jafa‘s work on Daughters of the Dust changed everything. He showed that Black cinematographers in Hollywood can create images as rich and painterly as anything in European art cinema. Jafa’s style moves between raw documentary realism and a dreamy, impressionistic beauty. He captured Gullah culture with a mix of ethnographic detail and pure poetry, both at once. When Young said, “It’s a crime that Arthur Jafa wasn’t nominated for a film like ‘Daughters of the Dust’,” he was calling out the way the Academy ignored work that didn’t fit its narrow, Western standards. Jafa’s shift into video art later on just proves how Black cinematographers often cross boundaries and refuse to be boxed in.

4. Malik Sayeed – Gritty Urban Realism

Malik Sayeed and Spike Lee made a powerful team. With films like Clockers and He Got Game, Sayeed established himself as a master of gritty, urban visuals – his style feels both real and stylish at once. People still look to Clockers as a reference point, especially in Oscar-nominated films that came after. Sayeed’s influence keeps showing up, inspiring younger filmmakers. He proved that Black cinematographers can set the tone for street cinema, inventing a look for urban life that Hollywood keeps coming back to, even decades later.

5. Rachel Morrison, ASC – Shattering Gender and Racial Barriers

Rachel Morrison made history in 2018. She became the first woman nominated for the Academy Award for Best Cinematography and the first to be recognised by the American Society of Cinematographers for a feature film. That same year, she broke new ground as the first woman to shoot a Marvel superhero film – Black Panther. Morrison isn’t Black, but her work on Mudbound and Black Panther shows how allies can use their craft to support Black stories with real care and skill. Mudbound’s director, Dee Rees, put it best: “I’m glad that people are recognising the craft of it and not making decisions based on tokenism; Rachel’s work is on the screen.” Morrison’s journey shows that breaking into cinematography as a woman meant facing down both sexism and racism, and that these barriers don’t exist in isolation – they pile up.

6. Autumn Durald Arkapaw, ASC – Marvel’s Anamorphic Trailblazer

Cinematographer Autumn Durald Arkapaw brought a whole new look to the Black Panther series when she switched things up, using anamorphic lenses and large format cameras for Wakanda Forever. Bradford Young, ASC, had a big hand in her landing the job. He told director Ryan Coogler that Autumn was the most talented up-and-coming cinematographer he knew.

Talking about the underwater scenes in Talokan, Autumn said, “It was vital to Ryan to create a deep-space feel down there. Things get dark. That tension, the texture, the murkiness – it throws the clarity off. Choosing to shoot it that way? That takes guts.”

In a world where giant franchises often swallow up personal style, Autumn’s work on Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, Loki, and Sinners stands out. She manages to keep her own visual voice, even inside massive studio systems. Autumn draws from her Filipina and Creole roots, weaving those influences into images that dig into identity, grief, and cultural legacy.

7. Tommy Maddox-Upshaw, ASC – Television’s Master Craftsman

Tommy Maddox-Upshaw took home the ASC Award for a half-hour series for his work on Snowfall. He’s a Black cinematographer, and when he accepted the award, he didn’t hold back: “Representation matters a lot. Thank you to the ASC.” He added, “I’m sensitive to brown skin tones because of my own cultural hue. When I watch shows, so many Black folks just look monochromatic. That’s not right. I have four sisters, and we’re all different shades of brown.”

Maddox-Upshaw is one of the Black cinematographers making serious waves in Hollywood television. His credits stretch from Snowfall to Empire, The Man Who Fell to Earth, and On My Block. He handles different genres with real skill. Early on, he learned a lot from working with Matthew Libatique. Watching other Black and brown people behind the camera made the dream feel real, something he could actually reach. Maddox-Upshaw insists on capturing the true variety in Black skin tones, not settling for that flat, uniform look you see too often. In doing so, he’s raising the bar for how Black cinematographers approach their work.

8. John Simmons, ASC – Multi-Camera Master and Visual Artist

John Simmons picked up his first Primetime Emmy in 2016 for his work on Nickelodeon’s Nicky, Ricky, Dicky & Dawn. Four years later, he did it again, this time for Netflix’s Family Reunion. He kept the streak going, adding a Children’s and Family Emmy for the same show in 2023. Simmons stands out among Black cinematographers in Hollywood, especially when it comes to multi-camera sitcoms. But he doesn’t just stick to one thing; he moves easily from documentaries to comedy, bringing sharp technical skills wherever he goes.

He is not limited to his work behind the camera. Simmons spent six years on the Television Academy’s Board of Governors and helped launch the ASC Vision Committee in 2016 as its first co-chair, way before all that, at just 15, he started shooting photos for The Chicago Defender, the oldest Black-owned newspaper in the country, founded way back in 1906. His photos ended up in some pretty serious places: the Getty Museum, Harvard Art Museums, and the Smithsonian National Gallery of Art.

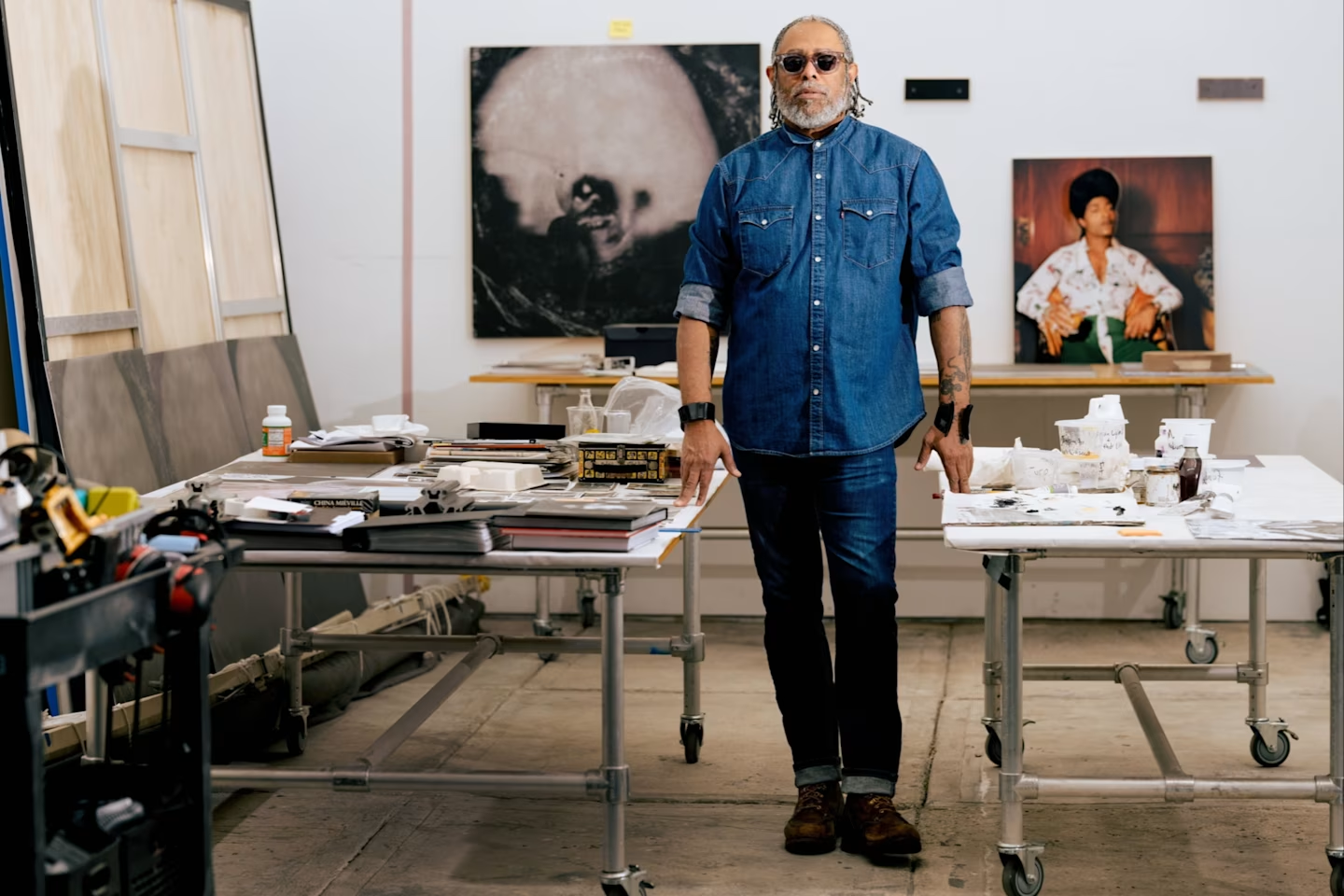

9. Henry Adebonojo – Documentary Excellence

Back in the early ‘90s, he worked alongside John Simmons as a camera assistant, often teaming up with the same circle of Black filmmakers. Fast forward, and he’s the cinematographer behind Black Art: In the Absence of Light; he not only films artists, but he truly captures their essence. Whether they’re in their studios, lost in the middle of creating something, or standing in a gallery with their work all around, Adebonojo finds ways to capture them honestly, with a kind of careful attention you can feel.

Among Black cinematographers in Hollywood, especially those focused on documentaries, Adebonojo stands out. He proves that documentary work isn’t just about knowing your gear; it’s about reading the room, being sensitive to the culture, and building trust. His portraits don’t just show faces; they capture the energy between artist and lens, especially when he’s working with Black artists and cultural leaders.

10. Checco Varese, ASC – Television’s Prolific Innovator

Checco Varese has made his mark on big TV hits like Tom Clancy‘s Jack Ryan and The Terminal List. He’s a standout amongst Black cinematographers dominating modern television and streaming, where so much of today’s visual storytelling happens. Varese keeps his work sharp and consistent, no matter how many projects he’s juggling. He’s proof that Black cinematographers aren’t just shaping “Black” stories – they’re mastering every kind of genre and format on TV.

READ ALSO:

- Fashion Icons in Film: When Heritage Shapes Cinematic Vision

- 10 African Filmmakers Dominating Global Cinema with Heritage and Vision

- 10 African Fashion Photographers Shaping a New Editorial Era

What Does This Legacy Mean for Cinema’s Future?

Young put it plainly: “I think it’s going to take some time for us to be in a place where [Black] technicians are recognised for what they bring to the table.” In particular, I believe that cinematographers generally view themselves as artists. It’s a journey because we don’t go to traditional American film schools.” That hits on something real: Black cinematographers often learn their craft through different routes: Howard University, local mentors, and indie film scenes. They build their own knowledge outside the big film school system.

Their collective impact isn’t just about personal achievements. Black cinematographers are changing the structure of Hollywood itself. They’re proving that beauty on screen can come from all kinds of traditions, that what we call “correct” technique is shaped by culture, not some universal standard, and that the future of cinema depends on opening the doors to new perspectives about what great cinematography really means.

Celebrate art, identity, and inspiration — explore Culture & Arts on OmirenStyles.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Who was the first Black cinematographer nominated for an Oscar?

That milestone belongs to Bradford Young. In 2017, he picked up an Oscar nomination for his work on Arrival, making him the first Black cinematographer ever recognised by the Academy. Remi Adefarasin, who was nominated for Elizabeth in 1998, was the last person of colour to receive a nomination in that category. Young’s nomination ended an 87-year-long exclusion of Black cinematographers, despite their significant contributions to the craft.

2. Why does representation in cinematography matter?

Cinematographers play a crucial role in determining how people appear on screen. Lighting, framing, and exposure – these choices determine whether Black faces appear beautiful, dignified, and truly seen. When Black cinematographers step behind the camera, they bring a cultural awareness that makes sure Black subjects get photographed with real care and respect. Instead of simply adhering to outdated techniques designed for white actors, they are adept at lighting Black skin to enhance its beauty.

3. What challenges do Black cinematographers face?

Honestly, the obstacles stack up. Gatekeepers often ignore or dismiss their work, calling their approach “technically insufficient” if it doesn’t fit a Western mould. Film schools and industry guilds often fail to provide them with the necessary support. Sometimes, people mistakenly believe that they are limited to shooting only Black stories. Even the tools – like film stocks and light metres – have been built with white skin in mind, so Black cinematographers have to work extra hard just to get the basics right.

4. How do Black cinematographers influence visual culture?

They shake things up, plain and simple. Drawing from jazz, hip-hop, African art, and their communities, Black cinematographers create new ways of seeing. Their work pushes against old rules, proves beauty comes in many forms, and shows that the way Black people appear on screen is deeply meaningful. It shapes how communities see themselves and how the world values them.

5. What can people do to support Black cinematographers?

Start by watching their films. Talk about their work, recommend it, share it. Push for them to get hired on big projects. Make sure film schools actually teach their techniques, not just the “standard” ones. Challenge the idea that there’s only one right way to shoot a film. If you’re in the industry, mentor newcomers. And remember – cinematography isn’t just about mastering a single look. Real excellence comes from many voices, many visions.