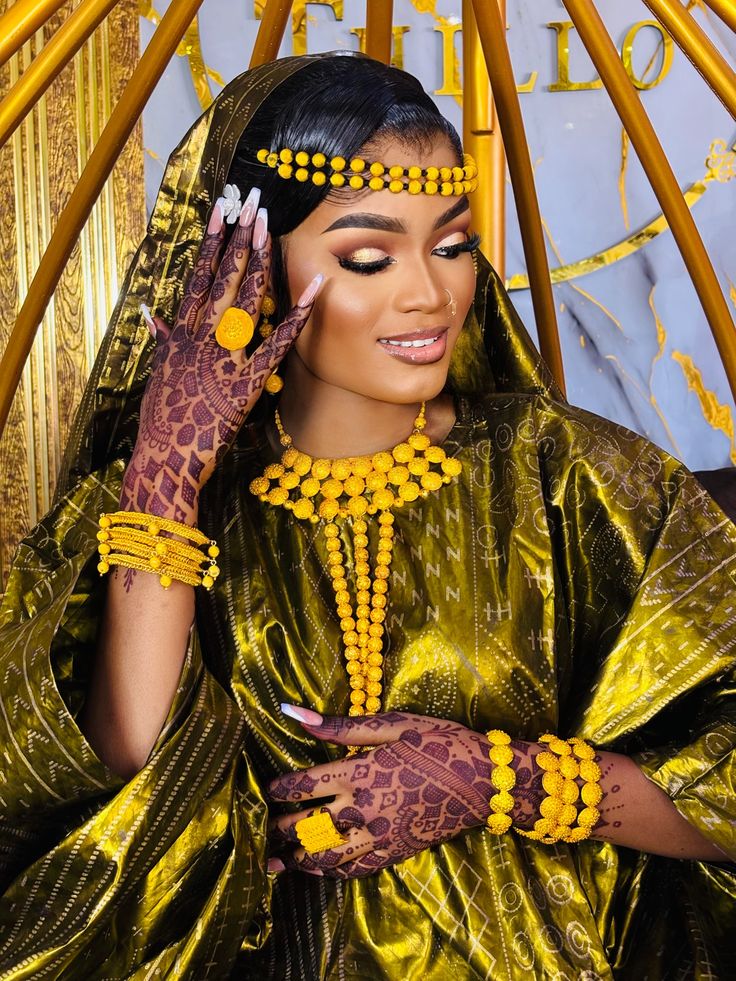

I always wonder why our brides always decorate their hands with henna during the wedding ceremony, how veils became our tradition, and how gold jewellery became part of our luxury. What stories are being written on their skin, stitched into their fabrics, and fastened around their wrists and necks? I carried these questions with me until the day I arrived at a coral-stone family compound in Zanzibar. I was standing there when women’s laughter rose instead of falling at the sound of the call to prayer. A young bride sat cross-legged on a woven mat, her palms lifted, as an elderly woman traced henna across her skin with the tenderness of someone writing history, not decoration. The paste had a faint scent of cloves and crushed leaves. Nearby, chiffon, silk, and satin billowed in the salt air, glowing like tide-lit water. Somewhere behind me, bangles whispered. And gold was everywhere: deep, warm, ancestral gold, not loud or borrowed, but ornamental.

The ceremony was not just a wedding preparation. It was a conversation between continents.

What I witnessed at Zanzibar is similar to the bridal preparation in Kano, Khartoum, and parts of the Sahel. This was not a coincidence; it was the living legacy of centuries of exchange between the Arabian and African worlds. The henna patterns evoked memories of the Gulf bridal nights. Veils styled like Yemeni or Omani wraps. Heavy gold jewellery echoing the souks of Jeddah, Muscat, and Dubai now adorns African brides whose grandmothers had never left their villages but whose traditions carried the ocean within them.

To this, I found that henna, veils and jewellery in African brides are no longer just a fashion; they are tools that carry stories of the Afro-Arab relationship

In this article, we unveil:

- How henna became both sacred art and social language across Afro-Arab bridal traditions

- Why veils in African weddings carry meanings beyond modest, signalling lineage, spirituality, and womanhood

- How gold jewellery evolved into both a beauty statement and financial protection for brides

- Where these traditions intersect today in modern African fashion and bridal styling

- How to honour these practices respectfully, whether you’re a bride, designer, or cultural observer

Explore how henna, veils, and gold jewellery from Arabian beauty traditions shape modern African bridal fashion and cultural identity.

Henn: The Ink of Blessing, Protection, and Belonging

The first time I watched a Sudanese-Arab bridal henna ceremony in Omdurman, the women did not speak much, but their hands told stories. Thick, geometric motifs crept up the bride’s forearms. Her feet were adorned with fine floral lattices. The patterns weren’t random. They never are.

“Henna is not decoration,” said Aisha al-Tahir, a bridal artist whose family has been preparing brides for over four decades. “Henna is prayer in colour.”

Henna’s journey into African bridal culture is inseparable from Arabian trade routes and Islamic spiritual life. From the Arabian Peninsula, Henna travelled along caravan paths through the Red Sea ports, Jeddah, Aden, and Massawa, then inland through Sudan, the Horn of Africa, and across Swahili coastlines, where Arab merchants settled, married, and built families.

In Zanzibar, I met Mariam Salim, a henna artist whose clientele includes brides from Tanzania, Kenya, Oman, and the UAE. “Swahili henna is softer, more floral,” she told me, dipping her cone into a bowl of paste dark as wet earth. “But the meanings – fertility, protection, joy- those come from Arabian roots.”

In Northern Nigeria, henna (locally known as lalle) is deeply woven into Hausa bridal rituals. What fascinates me is how Gulf-style patterns, bold geometric wrists, and filled palms now coexist with traditional Sahelian motifs. Brides blend styles, sometimes unknowingly carrying centuries of intercultural dialogue on their skin.

One elder in Zaria once told me, “Henna is how a woman enters marriage smelling like hope.”

And indeed, henna is always sensory. The cool paste feels refreshing on warm skin. The sharp green scent softens into sweetness. Women sing as they wait for the paste to dry. In Arabian and African cultures alike, henna night is not about the bride alone; it is about the community blessing her into womanhood.

Veils: More Than Modesty, More Than Fabric

In Muscat, I once watched a bride being wrapped in layers of sheer ivory chiffon, her face hidden for a moment before being revealed not to conceal her beauty, but to intensify it. That same choreography exists in parts of Mauritania, Sudan, and Northern Nigeria, where veiling the bride is not about hiding but about ritual transformation.

“Before the veil is lifted,” said Fatima Ahmed, a bridal stylist in Khartoum, “she is still a daughter. After, she is a wife.”

Veiling traditions in African bridal culture are inseparable from Arabian Islamic aesthetics, but they’ve evolved into deeply local expressions. On the Swahili coast, brides wear buibui-inspired veils paired with ornate crowns and layered jewellery. In Northern Nigeria, brides wear translucent wrappers draped over embroidered headscarves, often styled in ways reminiscent of Yemeni and Gulf bridal looks.

Historically, veils entered African bridal culture through Arab settlement, intermarriage, and Islamic scholarship networks. From Timbuktu to Harar, veiling was not imposed; it was adopted, adapted, and transformed into something culturally intimate.

Modern African designers now reinterpret veils through couture fabrics, lace, metallic threads, and sculptural forms, yet the symbolism remains: transition, dignity, reverence.

In Arabian culture, the veil has long been associated with sacred moments, weddings, pilgrimages, and rites of passage. In African bridal fashion, it becomes something even richer: a bridge between faith, femininity, and family honour.

Gold Jewellery: Adornment, Wealth, and Women’s Insurance

In Jeddah’s gold souk, I once watched a Yemeni bride try on a massive necklace, thick, heavy, and unapologetically bold. Her aunt whispered, “This is not fashion. The necklace is her future.”

That philosophy lives vividly in African bridal culture.

Across Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia, Northern Nigeria, and the Swahili coast, gold jewellery is not merely ornamental; it is security. It is portable wealth. It is dignity in tangible form. And its designs – elaborate chokers, crescent-shaped pendants, stacked bangles, and heavy earrings – carry unmistakable Arabian lineage.

In this context, women purchase gold not merely for fashion; rather, it serves as a practical means of banking.

In Kano, gold traders still reference styles by Arabian names: Makkah chain, Dubai set, and Yemeni bangles. I spoke with Musa Mai Gwalagwalai, a jeweller in Sabon Gari Market in Kano, who told me, “Our designs come from three places: Arabia, North Africa, and the old Sahel. But the soul is shared.”

Historically, Arab merchants introduced gold craftsmanship techniques along trans-Saharan and Indian Ocean trade routes. African goldsmiths then localised these forms, adding filigree details, heavier weights, and symbolic motifs that represented fertility, lineage, and prosperity.

In many African bridal traditions, gold is gifted not only by the groom but also by female relatives, reinforcing a matrilineal network of protection. It says, ‘Even if marriage falters, your dignity will not.’

INTERESTING READS:

- White Garments in Arabian and African Culture: Symbolism, Faith, and Climate Across Civilisations

- The Kaftan’s Soulful Journey: How an Arabian Robe Became Africa’s Most Powerful Fashion Icon

- Threads of the Desert: How Arab Thobes Shaped Sahelian Men’s Outfits

Fusion Without Borders: The Afro-Arab Bridal Aesthetic Today

In a Lagos bridal studio last year, I watched a bride being styled in layers: Gulf-style henna on her palms, Sudanese-inspired gold cuffs on her wrists, a Moroccan-style belt cinching her embroidered gown, and a Nigerian gele sculpted into a veil-like silhouette. When she looked in the mirror, she whispered, “I look like all my grandmothers at once.”

That, to me, is the essence of modern Afro-Arab bridal fashion.

Designers across Africa are increasingly drawing consciously from Middle Eastern bridal aesthetics not as imitation, but as inheritance. Saudi lace patterns appear in Nigerian wedding dresses. Emirati gold layering influences East African bridal jewellery. Yemeni and Omani veil styling shapes Sudanese and Somali bridal looks.

At the same time, African bridal fashion feeds back into Arabian couture. Moroccan caftans influence Gulf wedding gowns. Swahili embroidery appears on abayas. Hausa and Tuareg motifs inspire modern jewellery collections in Dubai and Doha.

This exchange is no longer historical; it is contemporary and alive.

“I don’t design African or Arabian,” said Leila al-Zahra, a Sudanese-Gulf fashion designer I met in Dubai. “I design the space between them.”

That space —flexible, diasporic, emotionally rich – is where today’s bridal beauty lives.

That evening in Zanzibar, after the henna had dried and the bride’s hands were lifted like offerings, her grandmother kissed her palms gently and whispered a prayer. The gold bangles chimed. The veil caught the light. The courtyard smelt of incense and warm tea. And suddenly, it was impossible to tell where Arabia ended, and Africa began, because in that moment, they were the same story.

Henna, veils, and gold jewellery are not trends. They are archives. They are maps of migration, faith, love, and endurance written on skin, stitched into cloth, and cast in metal. Every bride who wears them carries centuries of women before her, even if she doesn’t know their names.

That is the quiet power of beauty traditions: they survive because they feel true.

If you want more stories like this, where fashion meets history, where culture meets lived experience, and where Africa and the Middle East speak to each other in silk and gold, visit Omiren Styles and join our growing community of readers who believe that style is not just what we wear, but who we remember.

Have you ever witnessed a wedding in Sudan or Zanzibar? How do you sense the power of henna and jewellery in a ceremony?

Share your testimony with us at Omiren Styles

Because some traditions don’t fade — they travel.

From timeless tips to trendsetting looks — dive into Beauty on OmirenStyles.

FAQs

1. Why is henna so central to Arabian and African bridal rituals?

Henna occupies a unique position at the nexus of beauty, spirituality, and protection. Across Arabian and African cultures, henna is believed to ward off negativity, invite blessings, and mark transitions, especially marriage.

2. Are veils in African weddings only about modesty?

Not at all. While modesty is part of their symbolism, veils also represent transformation, dignity, mystery, and spiritual readiness.

3. Why is gold jewellery so heavy in both Arabian and African bridal fashions?

This is due to the social, financial, and symbolic value that weight carries. Heavy gold jewellery is not excessive; it is security, pride, and lineage worn on the body.

4. Can modern brides blend Arabian and African bridal traditions without losing authenticity?

Absolutely; in fact, fusion has become a traditional practice. Afro-Arab bridal culture itself is a product of centuries of blending.

5. Where can I see authentic Afro-Arab bridal fashion today?

Look to Northern Nigeria, Sudan, Somalia, Zanzibar, Morocco, and Gulf diaspora communities across Europe and the Americas. And platforms like Omiren Styles spotlight these stories with cultural depth and integrity.