For a long time, people wrote Africa’s history to suit their agendas, usually to excuse exploitation or erase real African achievements. Colonial writers painted Africa as a place without civilisation, full of simple people who had no real say over their own fates. Now, African historians are tearing down those old lies. Through research, books, and deep dives into culture, they’re taking back the narrative. Chinua Achebe put it plainly: for hundreds of years, Europeans wrote about Africa in ugly, distorted ways to justify the slave trade and colonialism. But by the mid-1900s, Africans finally reclaimed their stories. Today, historians from all kinds of backgrounds, novelists, anthropologists, and critics are united by a single goal: to tell Africa’s story from the inside, not through some outsider’s lens.

Meet ten influential historians reshaping Africa’s past and present, challenging colonial narratives and redefining how the continent’s story is told.

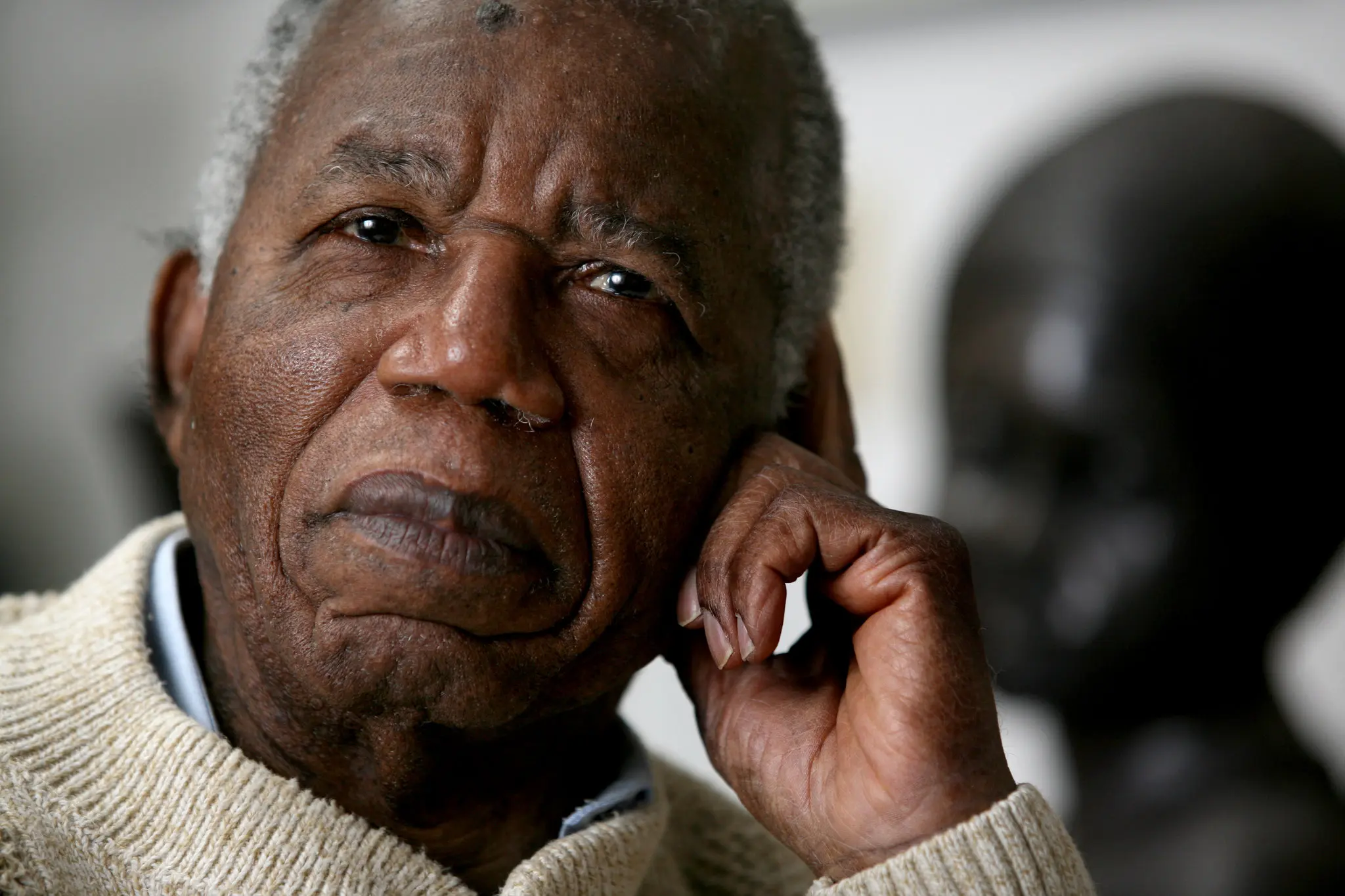

1. Chinua Achebe – The Voice that Changed Everything

Chinua Achebe, the Nigerian novelist, is often called the father of modern African literature. He never really liked that title; he thought it was a bit patronising and Eurocentric. But his influence is impossible to ignore. Achebe’s Things Fall Apart provided a platform for African voices, revealing the true nature of African cultures, free from colonial bias. Suddenly, African writers felt free to explore the real history, society, and culture of modern Africa.

One of the first African novels in English to make a global impact was Things Fall Apart. It has sold over 20 million copies and been translated into 57 languages. Achebe became the most read, studied, and translated African author ever. He showed that fiction could be just as powerful as formal history in challenging colonial myths. His work shattered the old European stereotypes, instead revealing the richness and complexity of Igbo society long before Europeans arrived.

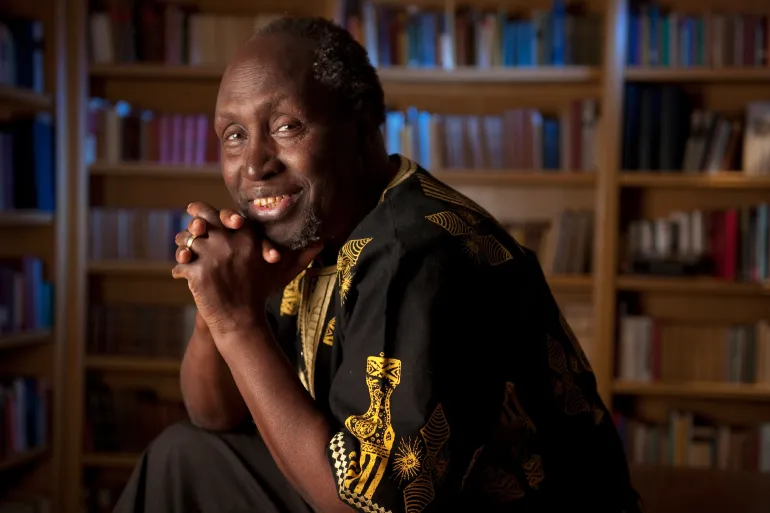

2. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o – Language is Power

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, from Kenya, takes a different approach. He sees language itself as a battleground. When he switched from writing in English to his mother tongue, Gikuyu, he made a bold statement: African stories belong in African languages. Why should anyone need European words to understand African life? Ngũgĩ’s work calls out the unfinished business of decolonisation; so long as European languages dominate African books, the old power structures survive. He pushes historians to do more than just record facts; they need to protect and celebrate Africa’s languages through their art.

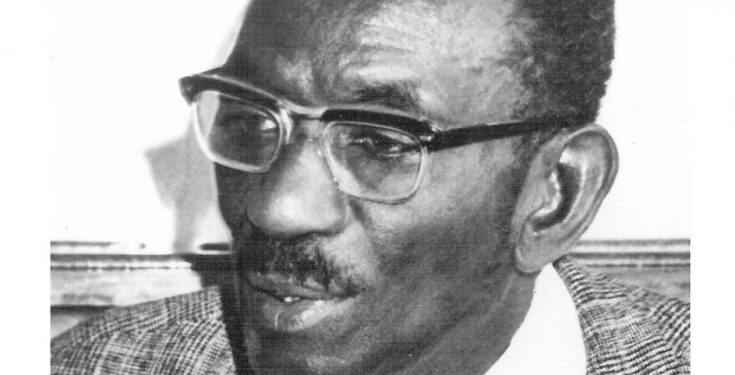

3. Cheikh Anta Diop – Ancient Africa, Rediscovered

Cheikh Anta Diop, from Senegal, didn’t just write about history; he rewrote it. He was a fearless historian, scientist, and Egyptologist who spent his life proving that Africa’s ancient civilisations, especially Egypt, were the true roots of later European cultures. During the 1950s, when the majority of people still held the belief in European superiority, Diop’s research posited that African civilisations were the source of inspiration for the West, rather than the other way around.

In 1966, Diop and W.E.B. Du Bois were honoured as the two scholars who shaped Black thought in the 20th century. Diop famously claimed that ancient Egypt was Black Africa’s creation and that the origins of Greek civilisation lie in Africa. His ideas sparked plenty of debate, but there’s no question he changed the way historians look at Africa’s past. Today, Dakar’s Cheikh Anta Diop University carries his name, a reminder of the mark he left on African scholarship.

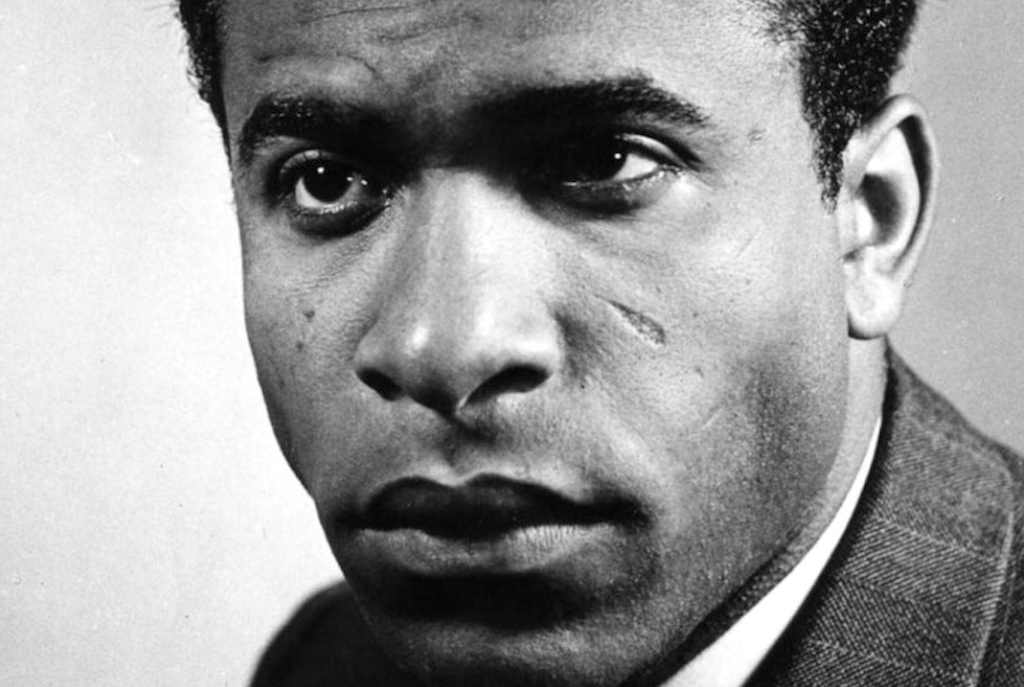

4. Frantz Fanon – Psychological Colonisation

Frantz Fanon grew up in Martinique, but his ideas helped fuel Africa’s fight for independence. As a psychiatrist and philosopher, Fanon didn’t just talk about political change; he dug into the way colonialism messes with people’s minds. In The Wretched of the Earth, he showed how oppression works on a psychological level, not just through violence but by worming its way into how people think and see themselves. For historians documenting Africa’s liberation, Fanon provided a way to understand how colonised people come to believe in the values of their oppressors. His work shaped how generations of African historians view decolonisation, not just as a political struggle but also as a battle for psychological freedom.

5. Yaa Gyasi – Tracing Slavery’s Generational Impact

Yaa Gyasi, a Ghanaian-American writer, tells a sweeping story in Homegoing. She follows two half-sisters from Ghana and traces their families across centuries of slavery and its aftermath. Many historians rely on academic texts, but Gyasi demonstrates how fiction can delve deeper; her novel effectively conveys the pain and legacy of slavery in a manner that textbooks simply cannot. She’s part of a new wave of African historians who know that sometimes you need storytelling to get at the emotional truth history leaves out. Homegoing proves you can tackle the legacy of transatlantic slavery and still create something that grabs readers everywhere.

READ ALSO

- 10 Environmental Activists Changing Our Planet’s Future

- Caribbean Literary Voices Shaping Global Culture

- 10 African Writers Shaping Modern Literature

6. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie – Making Nigerian History Accessible

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie takes on Nigeria’s tangled history, identity, and gender politics, but she tells these stories in a way that pulls people in. She writes about the Biafran War, modern life, and what it means to be Nigerian, weaving big ideas into novels that feel personal and real. A lot of academic histories get bogged down in jargon, but Adichie refuses to pick between being popular and being serious; she’s both. She stands for African historians who know that if you want history to matter, it has to reach people beyond university walls.

7. Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor – Lyrical Kenyan Histories

Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor, the Kenyan writer behind Dust, doesn’t just document Kenya’s history; she brings it to life with language that feels almost musical. Her writing dives into the pain of political violence, the messiness of ethnic tensions, and the scars left by national trauma. Owuor isn’t afraid to experiment with prose, proving that historical fiction can be ambitious and beautiful without losing its grip on real events. She shows that African historians don’t have to choose between art and accuracy; they can use every tool language offers to show what it actually feels like to live through history.

8. Maaza Mengiste – Illuminating Ethiopian Resistance

Maaza Mengiste, an Ethiopian-American writer, shines a light on parts of Ethiopia’s history that are often overlooked, such as Ethiopian resistance to Italian fascism, which she explores in Beneath the Lion’s Gaze. Mengiste doesn’t just tell another story about colonisation; she challenges the tired idea that Africa was always conquered or helpless. Her work shows Ethiopia’s fight against colonialism as a key chapter of African history, and she makes sure people recognise Ethiopia’s unique path. Mengiste joins African historians in their determination to preserve these stories.

9. Nwando Achebe – Advancing West African Scholarship

Nwando Achebe, a Nigerian-American historian and the daughter of Chinua Achebe, stands out as one of the key figures advancing West African history from within academic institutions. She’s not just a respected historian; she also edits journals, ensuring the work of African historians is seen, recognised, and taken seriously. Achebe shows that it’s not enough for African historians to publish new research. They have to build the whole system—journals, university programmes, and professional networks—that supports the next generation. She gets that real, lasting change means showing up everywhere: in classrooms, in publishing, and in the organisations where history gets shaped and debated.

10. Ayesha Harruna Attah – Pre-Colonial West African Societies

Ayesha Harruna Attah, a writer from Ghana, brings pre-colonial West Africa to life in her novels, like The Hundred Wells of Salaga. She doesn’t shy away from the tough parts, either; her stories dig into the region’s own slave trades, not just the transatlantic ones. Attah’s work stands out because she doesn’t sugarcoat history. She faces the uncomfortable truth that Africans played roles in slavery, but she doesn’t leave it there; she puts it in context, showing the larger systems at work. Attah proves that African historians and writers aren’t here to push propaganda. They’re after the truth, no matter how complicated it becomes.

How Are African Historians Changing Global Understanding?

African historians have challenged conventional notions about the continent. They’ve shown the world that Africa had sophisticated societies long before colonisation. European rule didn’t bring civilisation; it broke up what was already there. African resistance wasn’t rare or random; it was organised and constant. Unhealed historical wounds often initiate the major problems confronting Africa today. These historians make it clear: you can’t call scholarship “objective” if you ignore African voices. Western historians who claim neutrality but leave Africans out are just repeating old biases, no matter how careful their methods look.

What Role Do Scholars and Activists Play?

African historians in universities and activist circles collaborate closely with writers. They bring serious research, dig into archives, and build the institutions that help new histories stick. They show that it’s not enough to tell a positive story; you need evidence, peer review, and educational systems that actually teach these revised histories, not just treat them as side notes. Without that backbone, new narratives can’t take root.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Who are the most influential African historians?

A few names keep coming up when people talk about influential African historians. Chinua Achebe tops the list; his novel Things Fall Apart has sold over 20 million copies and has been translated into 57 languages. Cheikh Anta Diop also made significant contributions, sharing the spotlight with W.E.B. Du Bois as one of the most influential African intellectuals. Frantz Fanon changed how people thought about decolonisation with his deep dive into psychology and politics. Writers like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Yaa Gyasi are reaching readers all over the world right now. Their stories are making people talk about important issues.

2. Why do African historians use fiction?

Facts and dates may not always suffice. African historians use fiction because novels capture emotional truths, generational trauma, and everyday life in a way academic writing can’t. A book can reach a whole lot more people than a scholarly paper. These stories also call out the limits of colonial archives, showing that oral traditions and creative storytelling are real ways of preserving history.

3. What makes African historians’ work different?

African historians start from within; they focus on African experiences and voices, not outsiders looking in. In their historical research, they question old habits, take oral traditions seriously, and dig into the psychological effects of colonisation. For them, writing history is about power and who holds it, not just the past.

4. How have African historians changed academic history?

African historians have really shaken things up. They made universities confront the colonial bias baked into old research. They pushed historians to use more than just European archives, oral histories and local documents matter too. They also questioned timelines that treat European contact as the only milestone. Most importantly, they showed that Africans shaped their history rather than merely reacting to what Europeans did.

5. Where can people learn more about African history?

There are plenty of ways to dive in. Start with books by these historians. Check out journals like the Journal of African History, or take a course in a university’s African Studies department. Museums like the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art are packed with resources, and you’ll find podcasts and documentaries online, too. But honestly, nothing beats reading the original works by African historians themselves. That’s where you really get the heart of the story.