Body inclusivity in fashion is often discussed as a social issue, but its foundations lie in design systems, industrial production models, and historical standardisation. It is not simply a question of representation or visibility; it is a structural challenge embedded in the design, manufacture, distribution, and marketing of clothing. To understand body inclusivity meaningfully, it must be examined as an industry framework rather than a cultural trend.

The global fashion system was built on standardised body measurements, centralised manufacturing, and efficiency-driven production models. These systems shaped what bodies were considered “normal”, “commercial”, or “marketable”. As fashion globalised, these standards were exported across cultures, often replacing local body norms with externally defined ideals. Body inclusivity, therefore, sits at the intersection of design logic, economics, culture, and ethics.

This article examines body inclusivity as an industry structure rather than a social campaign, focusing on its historical origins, technical constraints, cultural dimensions, and the responsibilities of fashion institutions in addressing it in a sustainable and professional manner.

An in-depth analysis of body inclusivity in fashion, exploring design systems, production structures, cultural context, and industry responsibility.

Historical Formation of Body Standards in Fashion

Modern fashion standards are not neutral. They were formed through European tailoring traditions, colonial expansion, and industrial manufacturing models. Early Western fashion systems developed sizing and fit based on limited demographic data, often drawn from narrow population samples. These measurements became institutionalised through pattern books, tailoring schools, and, later, mass-production systems.

As industrialisation expanded clothing production, standard sizing became necessary for efficiency. Pattern grading systems were developed to scale garments up and down from a single base size. However, these systems were built on assumptions of proportionality that did not reflect global body diversity. The result was a framework in which one body type served as the reference point for entire populations.

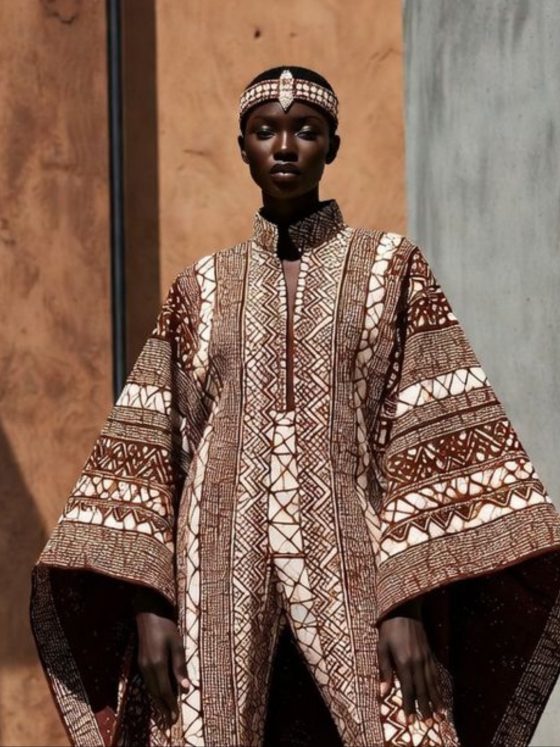

When Western fashion houses and manufacturing systems expanded globally, these standards were exported into markets across Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Local tailoring traditions, which once adapted garments to individual bodies, were gradually replaced by standardised sizing models. Over time, this created a globalised body hierarchy within fashion, where certain body types were structurally accommodated while others were marginalised by design limitations rather than aesthetic intent.

Body Inclusivity as a Design and Production Challenge

At its core, body inclusivity is a technical problem, not only a cultural one. Clothing design relies on pattern engineering, fabric behaviour, grading logic, and production efficiency. Every garment is built from a base pattern that is mathematically adjusted to produce different sizes. This process assumes predictable body proportions, which do not reflect real-world human variation.

Challenges include:

- Pattern grading limitations: Scaling patterns do not account for differences in torso length, shoulder width, hip distribution, or body structure.

- Fabric behaviour: Certain materials exhibit different properties across body shapes, affecting fit and durability.

- Manufacturing costs: Producing extended size ranges requires additional patterns, fittings, testing, and inventory management.

- Retail logistics: Stocking multiple size categories increases storage and distribution complexity and financial risk.

These constraints mean that inclusivity is not achieved simply by intention. It requires investment in design infrastructure, training, and the adaptation of manufacturing processes. Without structural change, representation remains symbolic rather than functional.

Representation vs Infrastructure

A critical distinction exists between visual representation and structural inclusion.

Representation focuses on:

- Model diversity

- Marketing imagery

- Runway visibility

- Campaign aesthetics

Infrastructure focuses on:

- Size availability

- Fit quality

- Product access

- Retail distribution

- Manufacturing capacity

- Design education

True body inclusivity depends on infrastructure. Visibility without access does not solve the problem. If garments are not available in extended sizes, are not correctly fitted, and are not distributed across markets, representation becomes disconnected from reality. Inclusivity becomes symbolic rather than functional.

Cultural Dimensions of Body Ideals

Body standards are not universal. Historically, different cultures have maintained distinct body ideals shaped by climate, labour systems, social roles, perceptions of health, and cultural values.

Examples include:

- African cultures in which fullness often symbolised prosperity and well-being.

- Different historical aesthetics shape East Asian standards.

- Fashion media and advertising industries shape Western thinness models.

Globalisation, however, created standardised beauty economies in which Western fashion and media systems increasingly influenced global body perception. This homogenization of ideals displaced local cultural frameworks and introduced external standards into societies that previously held different values.

Body inclusivity must therefore be understood not only as a design issue but also as a cultural negotiation process in which global fashion interacts with local identity systems.

The Role of the Fashion Industry

Fashion institutions influence body perception through:

- Design education systems

- Media representation

- Retail structures

- Advertising standards

- Runway casting

- Brand positioning

Their responsibility lies not in moral messaging, but in systemic design ethics. Ethical responsibility in fashion means building systems that:

- Accommodate diverse bodies in production

- Avoid harmful standardisation practices

- Provide access across size ranges

- Communicate responsibly in marketing

- Respect cultural body diversity

This responsibility is structural, not symbolic. It requires policy, training, investment, and institutional reform rather than performative campaigns.

What Genuine Body Inclusivity Requires

Genuine body inclusivity is built through systems, not slogans. It requires:

1. Design Education Reform

Pattern making, garment construction, and fashion education must incorporate diverse body modelling as standard practice, rather than specialisation.

2. Manufacturing Investment

Factories must be equipped to handle complex size ranges without reducing quality or fit consistency.

3. Pattern System Innovation

New grading systems must reflect body diversity rather than proportional scaling.

4. Retail Policy Change

Retail distribution must support access across sizes, not limit availability to symbolic categories.

5. Ethical Marketing

Marketing should reflect real consumer access, not aspirational imagery disconnected from product reality.

READ ALSO:

- What the Most Influential Fashion Pieces of 2026 Communicate Today

- Simplify, Then Elevate: The Quiet Power of Digital Minimalism in Fashion

Health, Function, and Design Ethics

A professional conversation on body inclusivity must also include health and functionality. Clothing should support movement, provide comfort, be durable, and be suitable for daily use across different body types. Inclusivity is not about aesthetic validation; it is about functional design responsibility.

Design ethics means creating garments that:

- Fit properly

- Support physical comfort

- Respect body diversity

- Avoid harmful messaging

- Prioritize usability

This framing keeps the discussion grounded in design responsibility rather than ideology.

Global Implications

As fashion markets expand across Africa, Asia, and Latin America, body inclusivity becomes increasingly relevant. Global brands now serve culturally diverse populations with different body structures, needs, and expectations. Without adaptive systems, standardised production models will continue to exclude large segments of the global population.

Inclusive design, therefore, becomes a commercial necessity, not just a social value. Brands that fail to adapt face market limitations, consumer disengagement, and structural inefficiencies.

Conclusion

Body inclusivity in fashion is not a campaign, a trend, or a cultural performance. It is a design systems issue, rooted in historical standardisation, industrial production models, and globalised fashion structures. Addressing it requires technical reform, institutional responsibility, and cultural awareness, not symbolic gestures.

A sustainable approach to body inclusivity recognises that bodies are inherently diverse and that design systems must adapt accordingly. The future of inclusive fashion depends on infrastructure, education, manufacturing reform, and ethical design frameworks, not surface representation.

When fashion treats body inclusivity as a structural responsibility rather than a cultural narrative, it moves closer to becoming an industry that genuinely serves global populations not through messaging, but through design.

FAQs

- What does body inclusivity mean in the fashion industry?

Body inclusivity in fashion refers to the design, production, and distribution systems that ensure clothing is accessible, functional, and well-fitted for diverse body types, not just visual representation.

- Why is body inclusivity a design and manufacturing issue?

Body inclusivity depends on pattern grading, production infrastructure, fabric behaviour, and retail logistics. Without structural design and manufacturing reform, inclusivity cannot be sustained.

- How did standardised sizing systems affect body diversity in fashion?

Standardised sizing systems were built on limited demographic data, creating global production models that exclude diverse body structures and reinforce narrow body standards.

- What is the difference between body representation and body inclusivity in fashion?

Representation focuses on visibility in media and campaigns, while inclusivity focuses on access, fit quality, size availability, and structural accommodation in fashion production.

- How can the fashion industry create sustainable body inclusivity?

Sustainable body inclusivity requires reform in design education, pattern systems, manufacturing processes, retail distribution, and ethical marketing frameworks.