“Opera has never been white,” says Givonna Joseph, a 67-year-old Black opera singer from New Orleans. “That’s just how it’s been sold. The real composers got pushed out of the story.” Joseph’s words cut through everything Western classical music has tried to teach us. We have been taught for ages that opera is exclusively associated with Europe and that Black singers are an exception rather than the norm. But if you dig into the parts of history people tried to hide—old burnt records, forgotten archives—you’ll find something else. Black opera singers were taking the stage long before America even existed. Their voices didn’t just join the art form; they shaped it. Should we remove them from the narrative? That’s not just a slip-up. That’s theft – passing off cultural exclusion as fact. Understanding how Black singers transformed classical music requires confronting certain realities. When racism held all the power, talent was no longer enough. Surviving meant choosing between staying true to your art and just making a living. Every Black opera singer on stage today stands on the shoulders of ancestors whose names were deliberately buried.

Explore how Black opera singers redefined classical music through resilience, artistry, and cultural reclamation, from 18th-century pioneers to today’s stars.

The Erased Foundations

Let’s go back to 1781. A 14-year-old girl stepped into the spotlight as an opera soloist in Saint-Domingue – today’s Haiti. She was free, a person of colour, and the first of African descent to star in a French opera. Soon, she was the leading female singer in Port-au-Prince. But for years, newspapers called her nothing but a “young person.” Only after her boss left her back wages in his will did we learn her name: Minette. Her erasure was no accident. It was deliberate, making Black singers invisible even as they filled concert halls.

Joseph talks about what came later – the violence of Reconstruction, the chokehold of Jim Crow, and segregation that shoved Black music and musicians into drawers or, worse, straight into the fire. Back in the late 1700s, New Orleans was the first U.S. city with a proper opera season. There were real, tangled networks of Black and white musicians, but those stories got buried too. All of this erasure had a point: to promote the myth that classical music belonged only to white Europeans and to deny Black brilliance.

So why do any of these stories still matter? This problem is primarily due to the persistence of the falsehood. Joseph says people look stunned when they realise she’s a Black opera singer. “Wait, you’re a Black opera singer?” they ask. That shock shows just how well the erasure worked. People genuinely believe that Black opera singers are a recent phenomenon, rather than a centuries-old tradition. Correcting the record is not about adding a footnote to a textbook. It’s about claiming what’s always been ours – showing that Black opera singers don’t just want a seat at the table. They built the house.

Why Did Breaking Barriers Demand Superhuman Excellence?

Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield was born into slavery in Mississippi sometime around 1819. She performed on the piano and harp, but her most notable talent was her soprano, which garnered attention during her 1851 concert tour. She faced significant challenges. Her manager refused to let Black people attend her concerts. Critics obsessed over the “novelty” of a Black woman singing opera, as if her talent didn’t count unless it shocked them. When she stepped onto the stage at New York’s Metropolitan Hall in 1853, people laughed. Then she sang, and critics raved. That breakthrough led her to Europe, where she performed for Queen Victoria.

But this story kept repeating. Black opera singers had to be extraordinary just to get a fraction of the credit given to average white performers. Take Marian Anderson. Opera companies wanted her, but she stuck to concert work – Lieder, oratorios, and spirituals. Howard University tried to book her at Constitution Hall in D.C., but the Daughters of the American Revolution shut the door on her because she was Black. Eleanor Roosevelt quit the D.A.R. over this and helped set up Anderson’s famous 1939 recital at the Lincoln Memorial. That only happened because the usual halls wouldn’t welcome Black artists, no matter their brilliance.

It wasn’t until 1955 – when Anderson was already 58 – that she finally sang at the Metropolitan Opera. Her debut as Ulrica in Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera cracked the colour barrier, but only after decades of proving herself. She’d spent her best years kept off the biggest stages, allowed in only when her career was winding down. That’s the real story behind so-called “meritocracy.” Black opera singers had talent to spare, but they didn’t have white skin, and nothing they did could change how those in power saw them. The myth that “merit” alone decides who succeeds falls apart here. Change came about because people forced institutions to face the truth – Black excellence had always been there, and it had always been ignored on purpose.

READ ALSO:

- 10 Black Cinematographers Transforming Visual Storytelling in Hollywood

- How African Drums Shape Global Music: The Real Backbone of Modern Sound

- 10 African Poets Shaping the Future of Global Expression

The “Black Voice” Question

Leontyne Price brought something new to opera. Her voice—smoky and sensual, unlike anything people expected— got everyone talking. Some critics wondered whether there’s such a thing as a “Black voice”. People still debate it, even though many agree that African-American singers often bring a velvety sound that’s difficult to forget.

But let’s be real. When white critics call Black voices “warm” or “rich”, they’re really saying, “different from what we’re used to” – and their standard was white. Black opera singers navigated a delicate balance. Sing “too white”, and people claimed they’d lost their roots. Show any trace of their background, and suddenly they were “too ethnic” for classical music. Price broke through all that. When she first sang Aida at La Scala in 1960, she became the first African American to have a solo at Italy’s top opera house. And in 1961, her Met debut ended with a forty-one-minute ovation. You don’t receive such a warm reception if your voice conforms to a preconceived notion.

Overall, it’s not about whether “Black voices” exist as a biological thing. What matters is that Black singers bring their stories and perspectives, shaped by history and culture. Their differences make opera richer, not weaker. And that, more than anything, is what audiences finally started to recognise.

How Are Contemporary Black Opera Singers Building New Foundations?

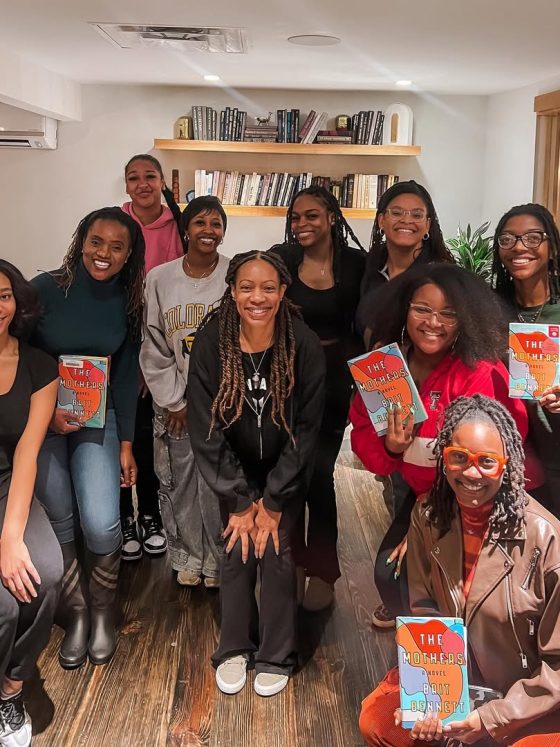

Denyce Graves didn’t just make her mark on stage – she founded the Denyce Graves Foundation, pushing for real equity and community in the American classical vocal world. Through her foundation’s ‘Hidden Voices’ programme, she shines a light on Black vocalists who’ve often been left out of the spotlight, like Mary Cardwell Dawson. Dawson, for example, started the National Negro Opera Company back in 1941—the first of its kind in the U.S.—so black artists could finally bring opera to broader audiences, especially in black communities in cities like Baltimore.

Now, today’s Black opera singers know that personal achievements alone aren’t enough. You see stars like J’Nai Bridges, Morris Robinson, and Russell Thomas lighting up international stages, but they’re also pushing for something bigger. While their presence creates opportunities, they can only effect lasting change by mentoring younger singers, preserving Black opera history, and challenging the enduring barriers that continue to hinder the art form.

Naomi André, who teaches at UNC and studies Black artists in opera, calls the moment a “golden age” for Black opera. However, not everyone believes that Black opera has reached its peak. Soprano Barbara Hendricks worries that soon we’ll be asking, “Where are the next Leontynes?” With music programmes vanishing from schools, especially for Black kids, she fears new talent will be rare – and short-lived.

Building a stronger future for Black opera means more than just putting new faces on stage. Representation without real support wears people out instead of lifting them. What’s needed is clear: funding for Black-led opera companies, new works by Black composers, opportunities for Black conductors and directors, and, most of all, a fundamental shift in who holds the power. Diversity can’t just be a buzzword – it has to come with real change.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Who was the first Black opera singer?

Minette, a 14-year-old free person of colour, took the stage in 1781 as an opera soloist in Saint-Domingue, now called Haiti. She’s the first documented person of African descent to star in French opera. Still, because history often erased Black artists, there were likely others before her whose names just didn’t make it into the records. In the United States, Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield, born into slavery around 1819, became famous in the 1850s.

2. When did Black singers first perform at the Metropolitan Opera?

Marian Anderson broke that barrier on January 7, 1955, stepping onto the Met’s stage as Ulrica in Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera. She was 58. Just a few weeks later, on January 27, Robert McFerrin became the first Black man to sing at the Met, performing the role of Amonasro in Aida. It took more than 70 years after the Met opened its doors in 1883 for such an event to happen.

3. Why were Black opera singers historically excluded?

For generations, Black singers faced exclusion due to systemic racism, Jim Crow laws, and the belief that classical music was exclusively the domain of Europeans. Money played a part, too – training wasn’t cheap, and opportunities were limited on top of all that, people in power sometimes destroyed records that could have proved Black artists’ contributions. Even the most talented singers couldn’t get past these walls until the civil rights movement forced real change.

4. How did Black opera singers influence the art form?

Black singers brought new life to opera, drawing on African-American musical roots and blending in gospel and spiritual styles. Their voices stretched what opera could sound like. They demonstrated to everyone that race does not limit greatness in music. When mainstream venues shut them out, they built their own – like the National Negro Opera Company – and kept history alive through their performances, even as written records disappeared.

5. Who are prominent Black opera singers today?

Today, singers like Pretty Yende (South African soprano), Lawrence Brownlee (American tenor known for bel canto roles), J’Nai Bridges (mezzo-soprano), Morris Robinson (bass), Russell Thomas (tenor), Denyce Graves (mezzo-soprano), and Angel Blue (soprano) are making their mark. You’ll see them at the Met, La Scala, the Royal Opera House, and other top venues around the world. They aren’t just performing – they’re guiding and inspiring the next generation, too.