From 1948 to the early 1990s, South Africa’s white-minority government implemented apartheid, which means “separateness” in Afrikaans. It was a harsh system of institutionalised racial segregation and discrimination. It set up a strict racial hierarchy that favoured whites and made it very hard for Black, Coloured, and Indian South Africans to get jobs, go to school, and move around freely. People had to leave their homes, families were broken apart, and generations grew up in terror, brutality, and constant monitoring. Sanctions and censure cut off South Africa from the rest of the world, causing widespread outrage.

But in the face of that injustice, resistance grew. Workers united, students staged demonstrations, churches became involved, and activists risked their lives. Nelson Mandela was one of the most important people in that fight. His long time in jail became a symbol of injustice and a source of hope. People in the country were on edge, caught between hopelessness and a firm conviction in freedom, until negotiations, internal resistance, and pressure from around the world slowly began to break down the system.

When democracy finally came in 1994, it changed not only the way politics worked but also the way people felt. A hurt country had to mourn, heal, remember, forgive, and somehow start over. And music helped people get over the fear, the fight, the grieving, and the waiting during this long voyage.

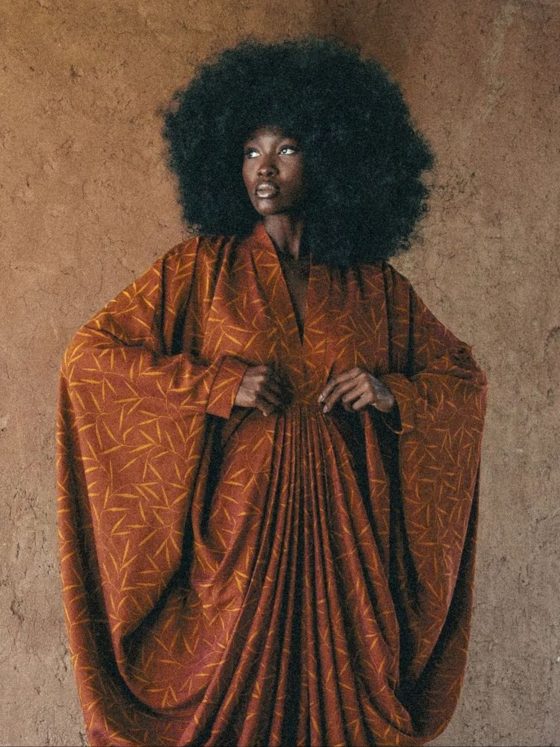

The journey through the turbulent 1980s and transformative 1990s was not only carried by politicians alone, but it was also echoed, challenged, celebrated, and sometimes mourned through music. Few figures more embodied this truth than five trailblazing women: Brenda Fassie, Rebecca Malope, Yvonne Chaka Chaka, Miriam Makeba, and Lebo Mathosa with Boom Shaka. Each artist represented a different tone of South African life: rebellion, faith, aspiration, exile, and youthful freedom. Together, their voices formed a soundtrack to resistance, resilience, and rebirth.

Below is a closer look at their music, cultural influence, and the ways their artistry mirrored the shifting identity of a nation on the brink of change.

A powerful look at the most influential South African female musicians of the 80s and 90s, their music, impact, and role in the nation’s journey to freedom.

Brenda Fassie — Rebellion, Truth, and Street-Level Storytelling

Brenda Fassie, often called the “Queen of African Pop, made music that was as bold and unpredictable as the country around her. Blending pop, township bubblegum, and Afrosoul, she became one of the most recognisable voices of the 1980s and 1990s. Hits such as “Weekend Special”, “Too Late for Mama”, “Black President”, and “Vul’indlela” captured rhythms that felt joyful while carrying poignant, sometimes painful narratives.

Fassie’s music mirrored the streets; she sang about love, betrayal, poverty, fame, and longing, directly addressing issues many artists avoided. Her work was fearless in tone and sometimes controversial, but that very honesty made her feel deeply authentic. When she sang about hardship, people believed her. When she celebrated, people felt free.

Culturally, Brenda represented rebellion and defiance. She refused to be contained by expectations about how women, particularly Black women, should behave. She lived loudly, dressed boldly, loved openly, and spoke truth to power without apology. Songs like “Black President” honoured Nelson Mandela and voiced hope for a new South Africa long before the transition arrived.

Brenda Fassie became a symbol of everyday survival. In a country fractured by injustice, she embodied a raw, unapologetic spirit, one that insisted life must be lived fully, even under oppression.

Rebecca Malope — Faith, Healing, and Spiritual Resilience

If Brenda Fassie represented defiance, Rebecca Malope represented healing. Known as the “Queen of Gospel, Malope emerged in the late 1980s with uplifting gospel music that offered spiritual refuge in dark times. Songs like “Ngiyekeleni”, “Udlalile Ngabantu”, “Shwele Baba”, and “Angingedwa” spoke to communities grappling with grief, economic hardship, and social instability.

Her gospel sound fused traditional harmonies with modern arrangements, making church-influenced music accessible to mainstream audiences. Her performances were emotional, powerful, and sincere; she wasn’t simply singing; she was ministering.

Rebecca Malope became a cultural figure tied closely to faith and endurance. While political protest anthems drew crowds to the streets, her songs comforted people in their homes, churches, and gatherings. She gave language to hope when despair seemed easier. For many, she symbolised the unwavering belief that liberation would arrive, not only politically but spiritually.

During the transition to democracy, Malope’s music evolved into gratitude and celebration while remaining rooted in humility. Her presence helped remind South Africans that survival of the soul was as important as political liberation.

ALSO READ

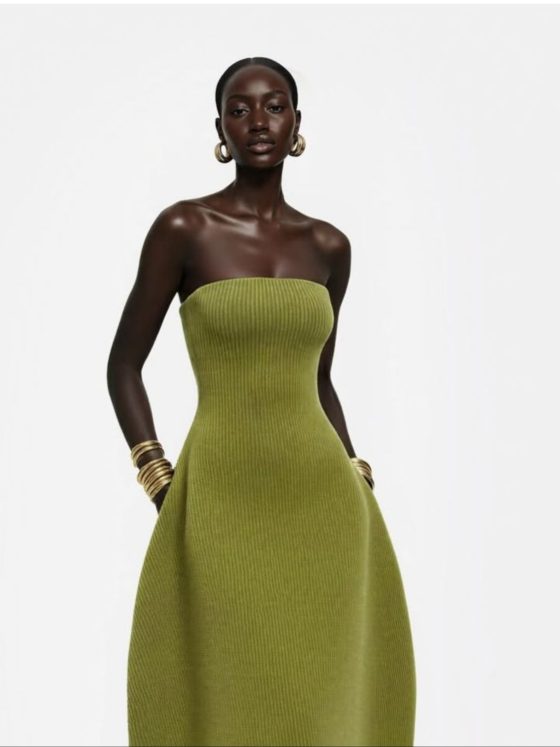

Yvonne Chaka Chaka embodies aspiration, dignity, and global ambition

Known as the “Princess of Africa, Yvonne Chaka Chaka became one of the continent’s most internationally recognised pop stars during the 1980s and 1990s. With infectious Afro-pop hits such as “Umqombothi”, “I’m Burning Up”, “Motherland”, and “Thank You Mr. DJ”, she crafted music that felt celebratory while subtly carrying messages about identity and pride.

Chaka-Chaka’s sound emphasised rhythm, dance, and melody, music designed for joy and communal togetherness. But underneath the upbeat exterior lay themes of cultural pride, African self-expression, and respect for heritage. Her image projected elegance and strength: glamorous yet grounded, modern yet unapologetically African.

Culturally, Chaka-Chaka represented aspiration and dignity. At a time when apartheid attempted to control representations of Black identity, Yvonne Chaka Chaka stood as proof that African women could be global icons without erasing where they came from. She has performed around the world, collaborated internationally, and later grew into activism, especially in health and humanitarian causes.

Her career reminded South Africans that democracy would not just be about political rights; it would also mean visibility, global participation, and the power to define one’s own narrative.

Miriam Makeba — Exile, Protest, and the Voice of the Struggle

Zenzile Miriam Makeba was an icon. Although Miriam Makeba’s career began decades earlier, her influence in the 1980s and early 1990s remained profound. Known internationally as “Mama Africa, she was exiled for speaking against apartheid, and she used her music worldwide as a tool of protest. Songs such as “Pata Pata”, “Soweto Blues”, and “The Click Song” ensured the world heard not only South African sounds but also South African pain.

Makeba’s music blended jazz, folk, traditional African melodies, and political expression. She sang in multiple languages, asserting pride in linguistic and cultural identity. Her performances were dignified yet powerful, subtle but unyielding.

Miriam Makeba embodied exile and moral conscience. While many artists within the country faced bans or censorship, Makeba carried their message globally. She testified before the United Nations, alongside activists, and helped international audiences understand that apartheid was not simply a political system; it was a human tragedy.

When they finally returned to South Africa after decades apart, her arrival symbolised reconciliation and endurance. Makeba’s legacy reminds us that the fight for freedom was both internal and international and that music could bridge continents in solidarity.

Lebo Mathosa (with Boom Shaka)—Youth, Freedom, and the Start of a New Era

In the 1990s, as apartheid collapsed and democracy emerged, a new sound exploded — kwaito, a genre rooted in township life, street style, and the energy of youth. At the centre was Lebo Mathosa, a dynamic member of Boom Shaka. Their hits like “It’s About Time”, “Thobela”, and “Free” pulsed through clubs, taxis, and neighbourhoods, signalling a break from past trauma to new possibilities.

Lebo Mathosa emerged as a cultural phenomenon. Bold fashion, blonde hair, and fearless choreography: she represented a generation not shaped only by struggle but eager for self-expression, fun, sexuality, and ambition. Her music and image challenged conservative expectations placed on women and sparked debate about identity, feminism, and empowerment in newly democratic South Africa.

Culturally, Lebo and Boom Shaka embodied youth culture and self-liberation. They did not ignore oppression, but their sound declared, ‘We have survived; now we claim joy, style, money, nightlife, and independence.’ For many young South Africans, kwaito marked the emotional beginning of freedom.

Lebo’s influence extended beyond music, opening doors for women performers to be unapologetically modern, provocative, and entrepreneurial. Her legacy lives on in contemporary African pop and global Afrobeats aesthetics.

A Collective Soundtrack to Transformation

Individually, each of these women represented a distinct emotional register:

Brenda Fassie — rebellion

Rebecca Malope — faith

Yvonne Chaka Chaka — aspiration

Miriam Makeba — conscience in exile

Lebo Mathosa—youthful liberation.

Together, they formed a layered narrative of South Africa’s journey. Their songs carried grief, anger, celebration, and hope. Some challenged authority head-on, others comforted communities quietly, and still others imagined futures beyond fear.

As apartheid crumbled and democracy emerged, their music didn’t simply document change; it helped people feel it, survive it, and believe in it. They proved that art is not decoration; it is memory, protest, prayer, and prophecy all at once.

New artists continue to sample their work, schools continue to study it, and families recall it from their childhood. Through rhythm and resilience, they turned a nation’s struggle into music and music into history.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Why were female musicians especially important in South Africa during the 1980s and 1990s?

Female musicians often expressed emotions and perspectives that political speeches could not. They gave voice to communities, challenged stereotypes about women, and helped people process fear, grief, and hope during massive national change.

2. Were these artists involved in politics directly?

Some were openly political, like Miriam Makeba and Brenda Fassie, while others, such as Rebecca Malope and Yvonne Chaka Chaka, influenced society more through culture, faith, and representation. All contributed to political consciousness, even when their music wasn’t overtly political.

3. How did Lebo Mathosa and Boom Shaka differ from earlier artists?

They represented a new, post-apartheid youth energy. Instead of focusing mainly on struggle, their music emphasised freedom, nightlife, fashion, independence, and modern identity, signalling an emotional shift toward a new era.

4. Do these artists still influence South African music today?

Absolutely. Their styles, courage, and storytelling shaped contemporary South African pop, gospel, Afropop, and kwaito and have since influenced artists across Africa and the world.